“The Hollow Desire to Populate Imaginary Cities,” 2014

Recently shown at Art in General, Curated by Anne Barlow

In the 1973 science-fiction film, Soylent Green, earth is overcrowded, polluted and saturated to the brink. Soylent Green, a supposed protein product sold by a corporation to the masses seeking nutrition, is discovered to not be made with the ocean’s plankton as the corporation purports it to, but made with human flesh – the only protein left available. Soylent Green is the more powerful substance coming after the ‘red’ or ‘yellow’ versions previously available.

I bring this up as a prelude to the film’s most dramatic scene; when one of the characters in the process of slowly dying through a euthanasia program, is exposed to what the earth and its natural environment looked like before the debris piled up: tulips swaying in the wind, deer grazing, lakes glistening…these scenes all flash before him on a giant screen. The scene is rudimentary and romantic (it’s coupled with Disney-esque music) as only a Charleton Heston flick can be, but it’s known for this attempt to pictorialize one of the most enigmatic questions, ‘what images do we see before we die’ ? This question, and the film’s processing of it, doesn’t implicate any moralistic position or an advent of judgement day per se. It is concerned mostly with the ocular event before our final breath. What is the proverbial ‘mind’s eye’ that supposedly stores all information pertaining to our specific time and place on the planet, and will it issue an epic download to the eyes? The images may appear to flicker in the blink of an eye –either in random order, chronological order, or perhaps even as a chorochromatic map[i] the kind that organizes diversified bodies such as land masses, airports, insects, dumptrucks or and takes into account qualities like the presence of heat or cold. How would this memory bank of ours color code the moods and states such as desire, longing, fear, boredom and rage ? Would personal events self-collect into pairings and groupings according to the degree of moral correctness or acts of shame? Or would they tie together into a tightly-woven matrix of good and bad, constructing something like the fractal design of a fly’s eye? How would we know, finally, that these images derive from our own personal source of stock footage, or if they are simply attached to molecules embedded in the generations of DNA we inherit.

Over the years, perhaps ten years or so, Magdy has been carefully processing images from mass media, from his immediate environment (Cairo, his hometown; Basel, his adopted town; and wherever he travels to), from information systems, archaeological history to scientific inquiry. These images make their way into Magdy’s parallel universe situated in a past/future collapse without contextual reference points or specifics. It’s an involvement in image-hoarding actually. What is distinct about the collection is a kind of pattern of forms that tends to emerge: construction sites, detritus and ruins, plant-life, recycling centers, provisionally built environments, decay, aggregate natural forms, surveillance cameras, biodomes, etc. Without being specific of time or place, the images suggest a ‘push-pull of a striving for progress against cycles of repeated failure: the future becomes less about promise than a continuous re-enactment of the present.’[ii]>

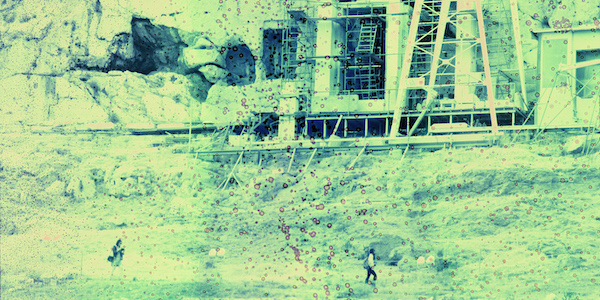

The images have provided the basis for a body of works on paper, textual work, installation, and, most recently, work with super 8 or 16mm film and photographs printed on metallic paper. Since early on, Magdy’s highly colored, precise drawings emitted a sometimes ironic sense of failure of the utopian promise and progress, not unlike the form a graphic sci-fi novel might take. Through acidic greens, hot fuschias and cobalt blues, Magdy’s dark wit and prophetically-inflected scenarios inhabit a kind of symbolist world in the not-too-distant future. Always present in the drawings is the power struggle between nature’s organic growth and man-made cultural/political artifacts. These are the works that first introduced Basim Magdy to a wider art world while he was working from Cairo.

The mature Magdy of late has loosened his grip on the graphic precision found in the works on paper and has immersed himself into the seductive qualities of time-based media, including within the films, soundtracks that he composes himself. In the films and photographs, he seems to be exploring more complexity or dimensionality and inverting the impulse towards narrative. High color remains a constant, signifying filter over a set of images as ‘clues’. Kaleidoscopic or psychedelic to some degree, Magdy’s color treatments emerge through an intentional process of chance and accident, or one could say, the film goes through a kind of optical trauma. Through a laborious process he calls ‘film-pickling’, the film stock or photograph is exposed to a concoction of household chemicals that eat away at the image, creating a slowly invasive overlay of abstract elements or fades. In the films, this process bears an even closer relationship to a kind of tactile persistence of forgetting; as the images progress, they also deteriorate – and one cannot help think of Benjamin’s assessment of Paul Klee’s Angel of Death, as a witness to the rise of debris forming out of the storm of progress.

“The Hollow Desire To Populate Imaginary Cities”, 2014, (commissioned by Art in General, New York) combines images culled from various parts of the world including areas around the Gowanus Canal, in Brooklyn (a highly toxic and polluted zone) although, again, time/place specificities are not meant to be relevant to the work. Within the serial matrix of images we see here for example: audiences watching a performing seal, to a car and a manufacturing plant, to a mosaic of an elephant that I want to say is at the Natural History Museum subway stop – in this series, whenever nature shows up, it is either performed, mediated, or a manufactured form of it. The work reminds me remotely of how Fischli & Weiss have created photographic inventories, alternating between a logic and a free association of banal forms. Like the artist’s own interest in photography as commentary, Magdy seeks out the moments where humor meets despair and exposes the insidious and manipulative effects of image consumption. Though with his added layer of a tactile manipulation, Magdy seems to be pushing these images further into the realm of optical subconscious. The work is persistently open-ended and offers a drift or scan over potentially charged environments. In most cases there are more questions than answers.

Many years ago, I had the opportunity to work with Magdy when we were both emerging in our careers. I became interested in this Cairene artist who was making visually compelling work uniquely his own, without the usual identity-driven, or ethnically-based marketing [iii] often encouraged out of regions. During a public talk, Magdy was challenged by an audience-member, an artist who seemed appalled that Magdy was not representing the socio-political context of Egypt enough in his work. It was my first time hearing Magdy defend his position as an artist who early on fought against allowing his ‘Arabness’ to be exoticized or used by the art world in order to service a validation of what that needs to look like. This has since become an important position Magdy has held fast to, refusing over the years to participate in group shows of ‘Arab or Middle Eastern artists’ as they appear and re-appear across Europe and the US with alarming regularity in more recent years. Magdy’s act alone has encouraged some peers to also to take back ownership of self-identification as an artist. Yet, looking back over years of his work and found in the content and imagery, one indeed finds a specific way of seeing, one that can only be cumulatively understood as formed through the condition of living Cairo. In Magdy’s case, Cairo is a paradigm for the pathos of the world’s humanity.

Basim Magdy was born in 1977 in Assiut, Egypt, and lives and works in Basel, Switzerland and Cairo, Egypt. His work appeared recently in exhibitions and screenings at La Biennale de Montreal, Montreal (2014), Art as a Verb, Monash University Museum of Art | MUMA, Melbourne, Australia (2014), MEDIACITY Seoul Biennial, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul (2014); Passerelle Centre d’art contemporain, Brest, France (2014); Trafo House of Contemporary Art, Budapest (2014); CRAC Alsace, Altkirch, France (2014); 13th Istanbul Biennial, Istanbul (2013); Tate Modern, London (2013); Centre Culturel Suisse, Paris (2013); Sharjah Biennial 11, Sharjah, UAE (2013); Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco (2013); Biennale Jogja XII, Yogyakarta, Indonesia (2013); The High Line, New York (2013); Askhal Alwan, Beirut (2013); Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin (2012); La Triennale: Intense Proximity, Palais de Tokyo, Paris (2012); Argos Art Center, Brussels (2011); Kunsthalle Wien, Vienna (2011); Institut Mathildenhohe, Darmstadt, Germany (2011); Mass MOCA, North Adams (2010) and Ateliers de Rennes – Biennale dʼart contemporain, Rennes, France (2010) among others. In 2012 he was shortlisted for the Future Generation Art Prize, Kiev and in 2014 he won the Abraaj Art Prize, Dubai.