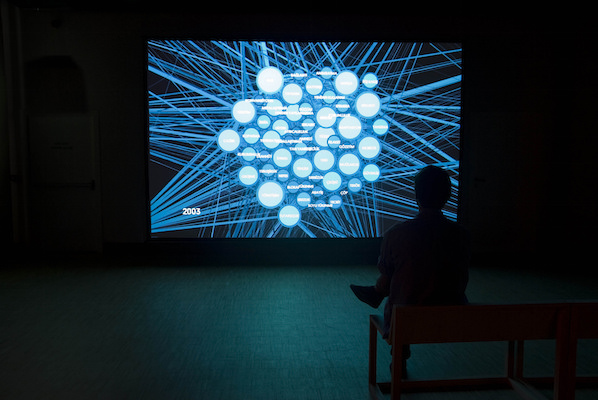

Exhibition view from “Becoming Istanbul”, SALT Beyoğlu, 2011 Photo by Serkan Taycan

Exhibition view from “Becoming Istanbul”, SALT Beyoğlu, 2011 Photo by Serkan Taycan

Today positioning the new art and cultural institutions outside the West – in places where local artistic and cultural productions have not historically found an institutional ground – stands as one of the most critical questions around cultural practice. Museums have traditionally been integrated into the narration of history, more particularly art history, as their raison d’être, and buttressed a biased perception of time and space in the name of universalism. Breaking with such understanding of the museum and other art institutions, how can we conceive new institutional models in contemporary practices outside the West that go beyond universalism, yet simultaneously engage with the global network and the local productively? First response to this question could be that there is no single formulation. Here, I would like to discuss a few examples based on my observations in Istanbul over the last decade in thinking the possibilities and potentialities that might be embodied in contemporary institutions vis-à-vis the societal challenges in which institutions operate. Accordingly, they should be considered as mere examples from a particular point of view whereas the ‘example’ appears as a concept that escapes from the antinomy of the universal and the particular.[i] I intend to underline certain characteristics of contemporary institutions by pointing out several exhibition examples that distinguish themselves from the traditional exhibitionary structures within the framework of locality – not determined by national boundaries. In these exhibitions, a form of responsiveness to the specific context of history and social environment is observed as a common tendency.

Example 1: “Never Again!: Apology and Coming to Terms with the Past”

In regions where freedom of expression is under pressure and democratic channels for it are weak, such as in the case of Turkey for most of its history, art and cultural institutions can function as platforms that trigger meaningful conversations around certain social and political events. One successful example to this is DEPO, an Istanbul-based art space for critical debate and cultural exchange that focuses on regional collaborations among Turkey, the Caucasus, the Middle East and the Balkans. DEPO’s 2013 exhibition “Never Again!: Apology and Coming to Terms with the Past” [Bir Daha Asla! Geçmişle Yüzleşme ve Özür] has explored various experiences of coming to terms with the past. Through a display of materials such as photographs, banners, official documents from private and state archives and testimonies of victims, this exhibition focused on how the act of state apology contributes to the development of a culture of democracy in society from a comparative perspective. It also showed how several states have come to terms with previous violations of rights, massacres and crimes of humanity as well as the meaning of an official apology through eight cases from around the world. In addition to the specific case studies, “Never Again!” also included a comprehensive map of the official apologies issued up to date as well as two books – first volume as exhibition catalogue[ii] and second volume[iii] – comprising of texts examining these case studies in depth and featuring contributions by authors and academicians working on issues related to confronting complex pasts, such as the colonialism of France in Algeria and the Srebrenica massacre, published in scope of this project.

Image 1: Exhibition view from “Never Again!: Apology and Coming to Terms with the Past”, DEPO, 2013

“Scared of Murals” [Duvar resminden korkuyorlar], another 2013 exhibition based on archival practice that contributes to the further understanding of the 1970s, uncovers the particular dynamics of cultural production during that period. Held at SALT, an institution that explores critical and timely issues in visual and material culture and a center for research and experimental thinking, this exhibition consisted of documentary materials along with the display of certain elements from particular exhibitions of the same period. The exhibition focused on peculiar conditions of cultural production in Turkey between 1976 and 1980 by taking the 1976 Antalya International Film and Arts Festival as its departure point, and ending with a photograph of a group of professionals with diverse backgrounds such as literature, theater, film and criticism among others, taken at the Kuşadası Culture and Arts Festival on September 11, 1980 – just a day prior to the military coup of ‘September 12’. In this span, the research and exhibition approached the period in reference to the exhibitions and public art projects by highlighting artistic positions in and around the Visual Artists Association [Görsel Sanatçılar Derneği]. Some key issues in the exhibition were artists’ rights, collaborations with workers unions, the role and position of art in public space, debates on censorship and the cultural policies of the state. In this respect, the exhibition’s importance, I think, lies notably in its contextualization of cultural production of the period within the economic, social and political conjuncture of the time. This kind of archival exhibition practice provides a social and cultural context to the art practices, which is absent from our memory and particularly that of young generation of cultural practitioners.[iv]

Image 2: Exhibition view from “Scared of Murals”, SALT Beyoğlu, 2013 Photo by Cem Berk Ekinil

Example 3: “İstanbul Eindhoven-SALTVanAbbe”

The exhibition model that favors local art histories does not necessarily have to be presented through documents though. Exhibitions can potentially situate artistic production from different contexts in conversation with one another. An alternative method in constructing a local art history can reveal itself through presenting the artistic productions within their specific historical contexts and exploring the differences in modes of production outside the Western canon. At this point, SALT and Van Abbemuseum’s collaboration on a series of three exhibitions – “İstanbul Eindhoven-SALTVanAbbe: Post ’89”[v], “İstanbul Eindhoven-SALTVanAbbe: ’68-’89”[vi] and “İstanbul Eindhoven-SALTVanAbbe: Modern Times”[vii] (spanning from the beginning of the twentieth century to the 1960s) – that brought together works from the Van Abbemuseum collection with selected local positions in Turkey are remarkable. As these exhibitions showed the art of the twentieth century through radical episodes, or moments in history, they brought into question the relationship between the Western artistic canon and the peripheral artistic productions in a broader sense of the geography and politics of culture. Dating back to the early twentieth century, for instance, a display of a painting from Turkey together with one of the classical pieces from Western art history gave the viewer a firsthand experience to see concurrent productions, and to critically evaluate the commonalities or differences between the two, contrary to the idea that modern art outside the West has been merely a reproduction of it. Initially, these exhibitions opened up discussions around how political and cultural modernization was perceived and interpreted in Turkey as well as other topics such as with the aesthetics, forms, contradictions and localities of interaction framing the artistic productions within the epistemic shifts and profound ruptures of the twentieth century – specifically in 1968 and 1989. In brief, they attempted to reveal the co-existence of ‘other’ actors and cultural productions outside the narration of West-oriented art history that have been an influential (yet under-recognized) part of modernity.

Image 3: Exhibition view from “İstanbul EindhovenSALTVanAbbe: ’68’89”, SALT Beyoğlu, 2012 Photo by Mustafa Hazneci

Example 4: “Becoming Istanbul”

The new emphasis on art and cultural institutions shows a tendency towards a deep and committed interest in local contexts in a global world order. However, this situation becomes more complicated with the franchise spread of the likes of Guggenheim and Louvre, or the international acquisition of archives by the Getty Research Institute. Thus, it also requires thinking of how an institution spatially engages with the local in addition to the historical links. Institutions may realize various projects to establish the relationality between the institution and the city, invent new approaches to the social problems of the city, and contribute to the development of social policies as well. SALT’s 2011 exhibition “Becoming Istanbul” [İstanbullaşmak] can be interpreted in relation to the institutions’ responsiveness to the accelerating urban transformations under the neoliberal policies, in this case within the context of Istanbul. This exhibition was shaped by rather contemporary subject matter, and it explored a wide range of timely issues in and around Istanbul, such as stereotypical understandings of ‘modern Istanbul’ and everyday problems in the city. The exhibition form included the visual productions of artists and researchers such as photography series, documentaries, news reports and architectural projects. As part of the exhibition, a database was created based on 80 concepts surrounding common opinions relating to the city and suggested new points of view.[viii] The database was formed in dialogue with audience through direct participation in the events as well as interactive programs in the exhibition. This database was put in circulation and made publicly accessible as a resource to develop further research projects into the urban later on. Also, the exhibition was accompanied by two parallel programs: ‘90’, a program of 90 events focusing on contemporary issues in Istanbul, and ‘The Making Of Beyoğlu,’ a series of workshops examining currently planned projects in Istanbul’s Beyoğlu district through other examples of spatial planning projects. Both programs were well attended by the city’s residents and investigated the problems and questions around the social life from different angles such as employment, education, housing, water consumption, waste and energy.

Image 4: Exhibition view from “Becoming Istanbul”, SALT Beyoğlu, 2011 Photo by Serkan Taycan

Examples 5 and 6: The 9th and 10th Istanbul Biennials

In the absence of permanent art and cultural institutions, biennials undertake the role of connecting art practices with the local in numerous instances today. The case of biennials can be discussed separately from other institutions primarily for its temporary structure. However, it is a fact that the increasing number of biennials worldwide instigates the experimental thinking on the exhibitionary practices, and fosters a critical engagement with the local. Such relationality can be developed through both time-oriented historical context and social ecology that surrounds us. Consequently, biennials intend to represent specificity, and this specificity is precisely their potential to be specific – site-specific as well as time-specific.[ix] Given this frame, I think the Istanbul Biennial is worthwhile to mention since it has been a key player that has influenced the dynamics of art practices in Istanbul in the post-2000s period. Although each edition of the Biennial deserves particular attention, I think that two of them can be interpreted complementary to the discussion of the locality of art institutions here.

The 9th Istanbul Biennial, curated by Charles Esche and Vasıf Kortun in 2005, set forth a value around the locality of Istanbul. The exhibition spread throughout the city and absorbed by it. In this sense, Istanbul was “not only the subject of the biennial but also its operational field”.[x] The biennial referenced both the real urban conditions and the imaginative portrayal in the world. It was formed in relation to ‘İstanbul’ as a metaphor, as a prediction, as a lived reality, and an inspiration for different stories, and embedded itself in this history and possibility. As for the exhibition venues, it took place in ordinary sites, such as an apartment block, a shop, a theatre and an office building, in reference to the everyday life of the city on the contrary of ‘exotic’ locales. The Biennial’s expansion beyond the formal and temporal limits of the exhibition was visible in other activities such as “9B Talks” that hosted academics, writers and curators for a year, and the publication “Art, City and Politics in an Expanded World”[xi] that presented a collection of perspectives of academics, artists, art critics and curators on art, the city and politics.

“Biennials of contemporary art… seek to be nationally and even internationally significant, by putting forward particular and supposedly incomparable local characteristics, what we might call ‘locality’… The challenge that we face is how to imagine and realize a biennial that is culturally and artistically significant in terms of embodying and intensifying the negotiation between the global and the local, politically transcending the established power relationship between different locales and going beyond conformist regionalism.”[xii] As is the case with the 10th Istanbul Biennial, entitled “Not Only Possible, But Also Necessary: Optimism in the Age of Global War”, the curator Hou Hanru turned the attention to the foundation of the Turkish Republic, and also problematized the official narration of history by the state throughout Turkey’s modernization process.The Biennial’s locality revolved around Turkey’s modern history as a twentieth century phenomenon. Dealing with the question of modernization, urbanization was considered as the most visible and significant sign of modernization. Thus, urban and architectural conditions of Istanbul became the starting point of inquiry. In order to critically reexamine “the promise of modernity,” the Biennial had picked some of the city’s most significant modern edifices and venues including the AKM (Atatürk Cultural Center), İMÇ (Istanbul Textile Traders’ Market), Antrepo, santralistanbul and KAHEM (Kadıköy Public Education Centre).

Image 5: Posters of 9th Istanbul Biennial (2005) and 10th Istanbul Biennial (2007) respectively

These aforementioned examples should thus be considered as institutional art practices in the context of a country founded through a radical modernization process as a social and political project, and more particularly, a city going through rapid urban transformations under severe neoliberal policies since 2000s. Similar experiences can be traced in many other regions outside the West where modernization has historically been experienced as Westernization to a great extent, and neoliberal policies manifest themselves in various degrees today. These examples, therefore, may help in conceiving new possibilities for art and cultural institutions in contemporary practices. In various ways, they have been innovative responses to urgent issues in art history as well as social environment as exhibition models to overcome entrenched structures and rethink the role of institutions in contemporary art practices. Thus, by developing socio-politically relevant exhibition models and challenging cultural-historical constructions, they offered new experiences of art and new forms of social engagement. As demonstrated by these exhibitions, contemporary institutional practices act as vehicles for the production of knowledge and intellectual debate. The exhibition practices in such institutions do not just include production and display, but also the production of discourse and the distribution of knowledge. The question then becomes how institutions can and should operate regarding their positions in the production and distribution of knowledge.