"The Sea Is Mine," Dictaphone Group

"The Sea Is Mine," Dictaphone Group

We met Abu Hussein when we were sitting once at Abu Adal’s kiosk in “Dalieh” in Beirut. He told us that he is one of the ten fishermen who were evicted from their sea-front rooms that were located under the Grand Café, a café on the southern coast of Beirut. These fishermen had been using these rooms for the past 40 years, as long as the café had been there. But the café did not used to look like it does today. Ever since its owners “upgraded” it in 2010, they saw the presence of these fishermen as undesirable, as a nuisance to the new image the café was trying to portray. And like that, the fishermen were evicted, given $4,000 compensation each, and moved to new fishermen rooms in Dalieh.

Today, the fishermen community of Dalieh is facing a similar battle. They recently received a lawsuit to evict the houses that they had informally built since the 1950s. The fishermen’s eviction signals a planned private real-estate development project in Dalieh.

Each location on the coast of Beirut has a different story. Accounts circulate about how the sea is being gradually closed off from the public. Studies are reported about how a law, or an exception to a law, or the trespassing of a law, is used by the political elite to enable the construction of big hotels and private sea resorts with exclusive access.

In fact, since the end of the Lebanese civil war in 1990, Beirut has been undergoing diverse forms of control over public space. It has particularly witnessed the gradual disappearance of coastal lands accessed by the public, which has been happening through a legalization of the de-facto privatization of the coastal line that occurred during the war years[i], and even before.

It is in this context that the project This Sea Is Mine was conceived. It is a site-specific performance and a research project that explored the concepts of access to the sea and public space throughout the city and anchored in Beirut’s seafront. The audience was invited to take part in a journey on a fishing boat from the Ein el-Mreisse fishermen’s port to Dalieh and Ramlet el-Baida beach.

During the journey, we stopped at each resort and revealed its land ownership, the laws that govern it, and the practices of its users. The project relied in its development on fieldwork, collaboration with several fishermen, collection of oral history as well as legal texts. Alongside the site-specific performance, the outcome of the project was a printed booklet that includes all research findings and oral narratives, as well as the produced maps. The booklet was distributed to the local fishermen community and in many venues in Beirut. It was also used as a tool during the performance.

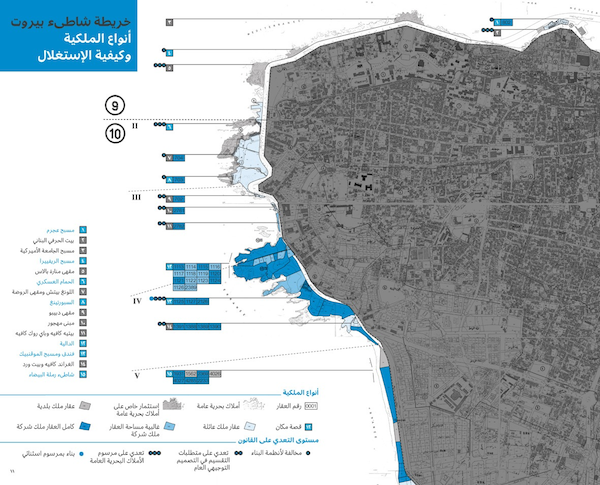

In reference to main map in the booklet, the trip started adjacent to Zaytouna Bay: a section of the sea-front corniche where the public is closely monitored by an army of private guards and surveillance cameras. It is a new marina area created over the rubble of a historic fishermen port now turned into one of the most expensive real-estate in the region.

The boat then stopped at the RivieraBeach Resort which lies in Zone 9 of the 1954 Beirut Master Plan and mandated against any building development. Yet it benefits from Law 4810 (issued in 1966) which allows for the exploitation of the public domain by private resorts.

The journey continues adjacent to the Bain Militaire: a massive beach resort with pools, restaurants and playing fields, owned by the Lebanese army and used as an officers’ club. All the buildings of this resort had been erected on public lands where the zoning regulation bans any form of contruction; the project is entirely illegal.

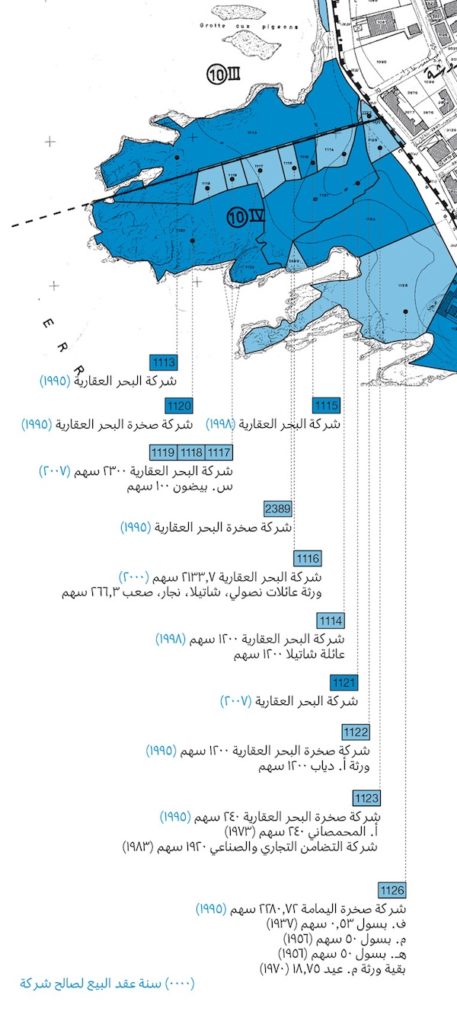

The trip continues, passing by several similar cases, and before the last destination, it exposes the case of Movenpick Hotel. This plot lies in Zone 10-IV of the 1954 Master Plan, which allows for building on 15% of the plot, with a maximum height of 9 meters, strictly for sports and maritime activities. However, during the civil war, a man from the Daher family bought this plot under the name of Merriland Company, and was able to purchase it in 1986. And through his connections with the political class at the time, he was able to acquire a building permit to execute a 10-storey hotel and resort on most of the area of the plot. In 1988, Daher was able to get a permit through a “presidential decree”, claiming that it was not possible to consult the specialized authorities!

Public Space as Use

Yet despite the above-mentioned conditions, or perhaps at least partially because of them, Beirut dwellers today still lay claim to a limited number of open areas in the city. These are used as “public” spaces in the sense that they are accessed freely and allow for an unconfined range of social activities to occur. Access to these spaces is secured through social and communal agreements through which their uses are organized.

One such case is our last destination in the journey: the Dalieh of Beirut.

Dalieh is the name of the large piece of sea-front land in Rawcheh area that stretches between the Movenpick hotel and the Corniche towards the sea. The land however is made up of several large private plots. Since the 1940s, this site has been declared an un-built land property of several families.

Yet “Dalieh of Beirut” is used today as one of the main public spaces in the city. It boasts two fishing ports and several informal seashore kiosks with a stream of visitors enjoying the sea, picnicking, bathing, and strolling. It is a main destination for swimmers and divers alike who come from different parts of Beirut to exercise their passion for jumping off of high cliffs into the Mediterranean waters – a practice that has been taking place there for as long as Beirutis can remember. It also includes a variety of social groups, such as Beiruti fishermen, suburb dwellers, Iraqi refugees, Syrian migrant workers and refugees, and others.

Although Dalieh is historically made up of plots privately owned by several Beiruti families, there are countless stories that recount that since the 1950s, it had been used as a renowned picnic/outing destination, getting very busy on holidays and weekend. Up until the 1970s, families gathered in it on Fridays, bringing their food, beverages, arghileh and a family member who played the Oud, Bozoq or Tabla. The activity was called “assayaran” and it referred to the practice of making a picnic/outing in “manateq at-tanazuh“, i.e. places of promenade/picnic/stroll. Additionally, up till the 1960s, Dalieh as well as Ramlet el-Baida beach were hosting sites for the yearly “Arb’a Ayoub” celebrations whereby residents hailing from different neighborhoods in Beirut would come together to march to the sea-front; the women would serve their traditional Beiruti dish, the most delicious “mfatqa” while the kids would fly their kites.

Describing how public space is practiced in Dalieh, it is important to understand it as the space to be shaped by the social groups that occupy it[ii], and as an outcome of communal practices. Dalieh is specifically interesting because it puts into question the modern accepted notion of public space that is tied to the state through the attribution of designated spaces in the city as “park”, “garden”, or other named ascriptions.

Dalieh opened new possibilities for understanding public space in Beirut as spaces of negotiation through daily interactions, and hence unpredictable by definition. This unpredictability was also a main feature of the performance itself.

Performance as Protest

Dictaphone Group was founded with the aim of marrying urban research to live art performances. The idea behind this collaboration is to popularize academic research by inviting audiences to build a relationship with the studied space and by making action-based work, which can be considered as a political action towards change. This is perhaps why the performance of “This Sea Is Mine” was described by the media as a “protest.”

The premise of the performance was that a group of people, compromising a small group of audience, a fisherman and a performer enter in a boat the private resorts in Beirut and attempt to swim there for free.

Armed by ancient laws that explained that the shore as far as where the water reaches is in fact public domain, we crossed the floating borders around private resorts and swam for free where others were swimming in return of over-priced day entries that ensure that only the rich and the elite are able to enjoy the sea. By placing the body of the performer and those of the audience in places where they are unwelcome, this live action turned into a protest claiming back the sea and the stolen public space in the city.

This interactive piece offers to the audience the opportunity to rebuild a lost connection to the sea, outside of the dominant experience of private resorts, to listen to the stories of the older fisherman who spent his whole life there, and to experience intimate stories, about other fishermen who were born by the sea and suffered from various threats of eviction. The audience also shared stories they know and the performance kept growing as we added these stories to the script.

Those who experienced the show were moved by different aspects of it. Some were angered when they heard how private companies and the political elite slowly took over the seashore and how they tricked families into selling their lands. Some fantasized about blowing up the high-rise buildings that block the sea view. Some expressed joy that they were able to see the city from another perspective, from the sea.

The project opened up a broader discussion in the city about public space. It happened at a time when other initiatives with similar concerns emerged in the city (Masha’a, Shatt Shattik.). We since reflected on ways to keep this performance going. The performance is currently being turned into a sound piece that would be available for everyone to download and experience.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………

As we write these words, statements and emails are circulating, protests taking place, and debates emerging about the current possible eviction of the fishermen community in Dalieh and the construction of a private resort on its land. When “This Sea Is Mine” was made in 2011, it aspired to help defend whatever remained of our coast. Today, a large group of us (academics, activists, users, designers, artists, urbanists, etc) aspire to defend Dalieh because its loss is not only to the fishermen, but to each and every one of us.

Map by Dictaphone Group | Design by Nadine Bekdache | Creative Commons License

Map by Dictaphone Group | Design by Nadine Bekdache | Creative Commons License