Monira: Okay, so there’s this painting of yours that really affected me when I was growing up called “Flying Desire,” I think you too, Fatima?

Fatima: Yes, for sure. It was so scary but captivating.

Monira: I felt in awe when I saw it. I was always looking at it.

Fatima: Also because of the way it was placed in the house, you couldn’t escape it. It was always there in front of you.

Monira: I mean the whole situation was so strange – the man in the painting had no eyes and was missing the top of his head and birds were flying out of it – all of this really made a big impression on me. Years later I made a short animated film “The Black Moon” where men had open heads with things coming out…

Flying Desire, Thuraya Al-Baqsami, 1985, Acrylic on canvas, 100 x 100 cm

Thuraya: You know the only time I exhibited this painting was when the Kuwaiti arts society was organizing a kind of Arab biennial and I submitted this painting to participate in the show. The organizers asked me then, “Thuraya, is this a painting of Frankenstein?” They were so critical towards the work to a point that they didn’t print the photograph of it in the exhibition catalogue – it was just left as a blank page with my name on it.

Fatima: So they let you take part but they didn’t print it? Why did they let you take part in the first place?

Thuraya: I don’t know, but I was so upset by their behavior that I decided never to show that painting again or to sell it. I felt very offended. I think they hated my painting to a point that it scared them.

Fatima: Yes it was frightening! Horror-inducing even… But another strong impression I received from this work was that a woman is powerless towards men…

Monira: Exactly!

Fatima: And next to it there was the other painting of women talking which added to that effect.

Thuraya: They’re all from the same period in the mid-1980s.

Fatima: They seemed like strange life lessons to me. When I saw them as a child, I felt that one showed that society is full of gossip – gossiping women – and the other was about how scary men are. That women only follow the orders of men, which came to them in the shape of birds.

Thuraya: My intention was to show that men can be selfish.

Monira: I know, but for me it really affected my ideas about women in general. I mean it made me begin to look down on the female gender.

Thuraya: I intended to show that the woman was begging the man for his emotions, for him to kiss her…

Fatima: It really made me hate being female.

Thuraya: I’m sorry, I didn’t mean it that way…

Fatima / Monira: (Laughs)

Monira: I was scared of it but I really loved it at the same time.

Fatima: It was fascinating, almost like watching a car crash. You know those people who stop on the side of the highway and can’t help taking a look at that person who just died. This painting felt just like that. It had a very disturbing power to it that you couldn’t look away from.

Monira: Anyway, during that period all of your work was very surreal, what made you drop surrealism later in life?

Thuraya: What made me stop using surrealism? The invasion.

Monira / Fatima: Really?

Thuraya: Yes, and it wasn’t just me – the whole art movement in Kuwait drifted away from surrealism after the war.

All of the artists who were working before the 1st of August 1990 were either working on traditional subjects (dhows, Sadu weaving, camels etc.), or were working on surrealist imagery. After the invasion, like many places that go through wars or disastrous events, a lot of things change in society and one main thing that changes is art. So for three to four years after the war, art works depicted people being hung, beaten, having their eyes gouged out…

Fatima: So it was mainly expressions of violence?

Thuraya: Yes and all the subjects became really dramatic somehow. Everyone used dark colors all the time. Some artists even felt that it was morally wrong to show work that had a hint of happiness or brightness to it. They felt obligated to be morbid in their work. There was an artist who even took all of his old paintings and reframed them with frames that had military camouflage patterns on them.

Fatima / Monira: What a great idea.

Thuraya: Currently, surrealism is much less apparent in the works of Kuwaiti artists in general.

Monira: Why do you think that happened?

Thuraya: Now they gravitate more towards experimental art, or abstract art. The work has become more about the patterns or the relation of colors and shapes, and even if the artist hasn’t mastered his medium, he can go online and find something he likes then copies it. And figurative art has almost completely disappeared. There were so many figurative artists before, but now I’m one of the very few that are left.

Monira: And you affected us as well, we’re both figurative artists.

But going back to surrealism, it kind of disappeared on a global scale, not just in Kuwait.

Thuraya: Of course, but in this country I think the main event that helped that happen was the war.

Funeral, Thuraya Al-Baqsmi, 1985, Acrylic on canvas, 100 x 120 cm

Fatima: But mom, how come you say your work isn’t critical of society? You have so much political art you’ve made, and even those two paintings we were very affected by, there was a clear social critique in them, or not?

Thuraya: Yes for sure there is a critique in them, you’re right.

Fatima: So let’s say it’s genetic.

Thuraya: Don’t you want to hear about what I felt when I saw you drawing as children, especially during the war?

Fatima / Monira: Yes.

Thuraya: Despite the horror you were living, both of you were very daring. You didn’t have the feeling of real danger or threat towards you.

Fatima: I mean we were just kids. I was nine, and she was seven.

Thuraya: Exactly, so you never expected or imagined that the soldiers could come and arrest you or kill you because of some drawings you’ve just made. You were just upset that your normal life had been disrupted, and the reason for that disruption was the soldiers outside. I’ll never forget Fatima’s drawing where she painted the Iraqi soldiers as monkeys with tails, and Kuwaiti strong men were beating them up.

Monira: And I drew that hamburger with a soldier inside it. (laughs)

Thuraya: So by making these drawings I think both of you got rid of a lot of the fear and anxiety caused by the war situation. That’s why I did my best to give you colors and paper so that you’d continue that way.

Fatima: But you hid them after we drew them?

Thuraya: Of course! As soon as you were done I hid them away. They would’ve burned our house down if they saw them.

Fatima: Where did you hide them then?

Thuraya: Inside the AC.

Monira: Really?

Thuraya: Of course, they were dangerous drawings.

Monira: But you were painting a lot too during the war, why?

Thuraya: For the same reason – to help myself deal with the horror and depression I was experiencing, the feeling that I might or might not wake up to see the sun tomorrow.

Fatima: Were you also painting scary things? Using surrealism?

Thuraya: No, it was mostly symbolism that I adopted during this time. My figures became pale and white, and their eyes became totally hollow. Those eyes with big pupils completely disappeared, and they became dark blind eyes.

White faces like dead people – I was painting mummies!

Fatima: Didn’t the soldiers react to the paintings?

Thuraya: Yes, once they came into the house and saw my paintings, and one of them said, “Why are all these people bald? Don’t they have hair?”

Fatima / Monira: (Laughter)

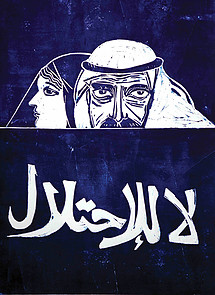

No to the Invasion, Thuraya Al-Baqsmi, 1990, Linocut print, 40 x 30 cm

Monira: You’re an impatient woman, correct?

Thuraya: Yes.

Monira: You can’t sit for months painting one single work, right?

Thuraya: Why would I? It’s torture!

Monira: I mean there are artists who sit and work on a painting for a whole year. But I know you work very quickly, like spending two or three days, a week, or two weeks maximum on a single work.

Thuraya: Right.

Monira: So I think you’ve also affected us in the way we spend time on our work. Even though it isn’t a direct influence, it’s a strong influence nevertheless. We’re both very impatient with our work. We work very quickly on one thing, and if we don’t finish it now, it’s never done. (laughs)

Thuraya: True. There are artists who work on several pieces at the same time, I can’t do that either. I work on each piece individually until it’s done.

Fatima: So you can’t make two things at the same time? I have the same problem.

Monira: Me too!

Thuraya: That’s why I hate oil paints, because I have to wait.

Monira: You always use acrylics which dry faster – a symbol of your impatience! How do you think art will develop in the future? For us for example?

Thuraya: You both have big challenges ahead. I mean it’s known what I do – I’m a painter. But you have installations, videos, sound work – a lot of complicated issues that involve technology and different effects…All these things that I never tried, never will try, and honestly don’t want to try or experience.

I don’t speak the same visual language you do. You use music, film, photography, then you also collaborate with different people – you start projects that others help you finish…

I feel I’m Louis the 16th’s armchair, and you two are IKEA chairs.

Fatima / Monira: (Laughter)

Thuraya: I’m the old fashion and you’re the new fashion. Let me tell you about when I visited a museum in Berlin in 2001, it was showing a collection of German paintings and sculptures which I found to be very inspirational and was really satisfying. Four years later I went to the same museum only to see it had transformed into small dark rooms with video art exhibited inside – a video of a fly buzzing, a woman giving birth among other strange things – which made me feel that this world isn’t my cup of tea. It just isn’t my world.

Monira: What about the videos we make?

Thuraya: I think your film “Wa Waila” (Oh Torment) is a masterpiece, one of your best works so far. Of course I was the producer, with the 200 KD budget I provided.

Monira: (Laughs) But you had fun making it with me?

Thuraya: Of course, I experienced what it was like to work on a film for the first time. I was happy to work on it, but its not the kind of thing I would want to make myself.

(Fatima) Your kleenex box was interesting too.

Fatima: What did you think of it?

Thuraya: Both of you have a prominent critical side in your work. Even though “Wa Waila” is just a music video, part of it depicts a critical view of society. The big Kleenex box (Mendeel Um A7mad) was a beautiful installation piece, but it also presented a critique of society. In your works I’ve noticed you can’t let go of this feeling of criticism towards society, towards yourselves, towards others, and you always show it in a very funny way. Because you know that through humor concepts are understood faster by the audience.

Fatima: But Monira’s work isn’t funny, is it?

Monira: I never mean for it to happen at all, but people always find it funny and laugh.

Fatima: Really?

Monira: Yes, when I showed the film in Dubai people were pissing themselves laughing.

Fatima: At “Wa Waila”? How is that possible? It’s so tragic!

Monira: Right? That’s what I intended, but people are always laughing, its so strange.

(cut)

Monira: Mom, what do you think of our work?

Fatima: Imagine we weren’t your daughters, how would you perceive it independently as an artist?

Thuraya: Each one of you has a different style of course, it isn’t the same.

Monira your work is based more on fantasy, it’s related to spiritual matters, divinities.

Fatima’s work as an artist is more pragmatic. It’s a critique of society, exhibited in a way that satirizes it. Whereas your work (Monira) contains a story in which a tragic mood is very apparent. It reminds me of saintly things.

As a whole, considering your age and how much work you’ve produced, I think both of you have reached a good point in your artistic careers, and I’m not saying this as your mother. Also, I have to add that neither of you has ever tried to imitate my style, or use the techniques that I use in my work. Even when you were kids you both had your own individuality, your unique worlds, and I think it’s a good thing that we’re all very different.

Monira: You really think your work didn’t affect us?

Thuraya: Yes, I truly believe that. The only thing that I feel I contributed in a meaningful way is that I gave you the opportunity to develop yourselves as artists. Even when I was in the prime of my motherhood and you were still children, I never put any pressure on you and said things like “art isn’t important, studying is important.” Not at all. Whenever you had the desire to paint or draw you were welcome to do so. The thought of school grades or studying never crossed my mind. I provided you with the best environment I could: a good working space, high quality art materials (my own materials), and at the same time I encouraged you to participate in different exhibitions whenever there was a chance to, like children’s art shows. When you would win prizes or had successes this would motivate you to keep making more work.

But you never painted like I did. Not once did I see any of the figures or symbols I use in my work in your drawings.

Monira: But I’ve noticed that in your work you always depict people, and in our work we are also always portraying people.

Fatima: Yes, there is a clear figurative link.

Thuraya: I’ve always loved figurative art and I still do.

Monira: But this love for figures really affected us in a major way, even though you didn’t mean for it to happen, or whether we consciously thought about it.

Fatima: All our work has the face of a person in it because of that. We have no abstract work.

Monira: Yes, or anything that simply contains scenery or landscapes for example.

Fatima: Nothing without a person in it.

Monira: This is clearly a tendency that came from your side.

Thuraya: But I think this also comes from your personalities – you’re social, you like people.

Monira: No, when I was a kid I was completely anti-social. (laughs)

Thuraya: I don’t know, but I never imagined you would draw a drawing without a person in it. During the war you drew caricatures of the Iraqi soldiers too. When Fatima moved to Miami and studied lithography and printing, the image of a person was always there in her prints.

Monira: But why is it that you like portraiture so much? Why do you always paint people?

Thuraya: Because I’ve met so many people in my life, I feel like their likenesses are imprinted inside of me, and I have to let them out one by one so that there’s space for new faces.

Fatima: So when you were young you painted faces too?

Thuraya: Of course. I remember I had an Egyptian art teacher when I was middle school, Ms. Hamdiyya, and she used to try to teach me how to draw Egyptian farming peasant girls – their big eyes and round faces – so she influenced me in this way.

Also, when those guys went to the moon and that whole period of space exploration started, I was very, very affected by these ideas about outer space.

Monira: Really? I never knew!

Thoraya: You can’t imagine how much it inspired me. The first novel I wrote was called “The Bride of Mars.” It was a story about a girl called Zahra I think. Aliens land next to her house and abduct her on their spaceship, then she’s taken to Mars where she meets a prince and marries him. I was fifteen when I wrote it. I sent my entire hand-written notebook of the story to a magazine called “Usratee” (My Family), and the man in charge there wrote back to me saying it was too early for me to publish a book, and that I should read more. The sad thing was that he never sent my notes back…