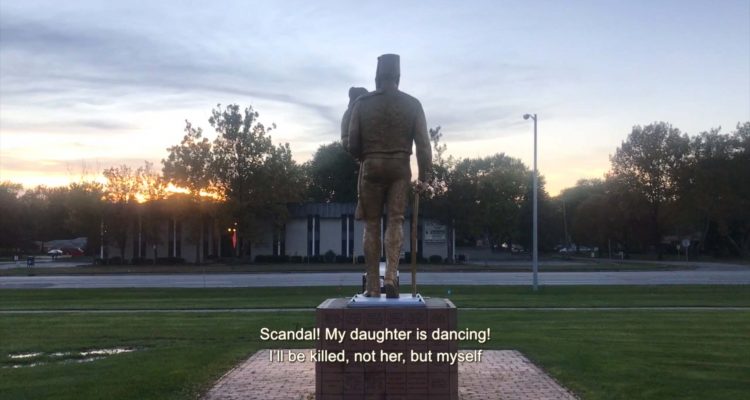

Turath aw Hadara, in collaboration with Jose Luis Benavides,

still image, 2019, video, 17 minutes 30 seconds.

Turath aw Hadara, in collaboration with Jose Luis Benavides,

still image, 2019, video, 17 minutes 30 seconds.

ArteEast is pleased to present an interview with artist Qais Assali as part of our Artist Spotlight series.

Qais Assali is an interdisciplinary artist/designer born in Palestine in 1987 and raised in the United Arab Emirates before returning to Palestine in 2000. Assali taught in visual communication at Al-Ummah University College, Jerusalem, and at An-Najah National University, Nablus. He is currently an Andrew W. Mellon Assistant Professor of Digital Design at Vanderbilt University, Tennessee. He was a 2019-21 Core Fellow at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. He was a 2018-19 Artist/Designer-in-Residence and a Visiting Assistant Professor for the Critical Race Studies Program at Michigan State University.

Assali holds four degrees in visual arts from Palestine and the US. He completed a BFA in Graphic Design from An-Najah National University 2009 and a BA in Contemporary Visual Art from the International Academy of Art Palestine 2017. He simultaneously completed an MFA in Photography from Bard College, New York 2019, and an MA in Art Education from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois 2018.

ArteEast: Can you tell us about your work in general and the main themes you return to in your practice?

Qais Assali: As a Palestinian artist/designer, I commercialize, politicize and displace causes, ideologies, sites, jokes, names, relationships, barriers, or subject positions based on unsmart practical geopolitical conceptualism and design.

I seek to complicate historical hierarchies. I am the result of my generation, experiencing the entire Second Intifada and trying to frame or shape it in different ways. These historical narratives fuel my passionate gaze toward the Middle East by subverting notions of oppression and victimhood. My work shows how the case of Palestine is more broadly connected to the problems of the Arab world and the whole world and to see the historic Palestinian relationship to colonization and imperialism.

My image-based practice seeks to engage and subvert national geopolitical power dynamics. I stage questions between sites related to my own identity and locale to debunk metaphoric surroundings and contested geographies. I make a satire of an initial assumption of likeness. I start with an existing superficial connection between sites based on a surface likeness – a tenuous crossover related to a name, a language group, a resemblance in layout – one site is often a form or a copy of the other. Through the dubious link to the original, the copy begins to ask questions about the status of the original.

My art and design practice includes photography, video, installation, performance, and graphic design. When working with archives, I engage with issues of time and memory, collective trauma, and diasporic doubling through investigations of historical events, the deconstruction of my role as author, and my own subjective position.

AE: Since 2009, you have been teaching visual communications at various institutions such as Al-Ummah University College in Jerusalem. Recently you accepted a position as the Andrew W. Mellon Assistant Professor of Digital Design at Vanderbilt University’s Department of Art. Can you speak about your experiences teaching? Has the act of teaching and conversing with students taught you something in turn or influenced any aspect of your practice?

QA: I have been exposed to different kinds of academic spheres from a very early age. I was raised by Palestinian educators, so my initial familiarity with teaching comes from there. Then, directly after my first BFA, I started teaching Graphic Design in Nablus in 2009. But I always had multiple roles at the same time. I was often juggling various identities: artist, designer, student, and educator. And because of having these simultaneous experiences, they often blended into one another.

I explored these connections during my MA in Art Education and my MFA, which I was completing at the same time in the US. The link between the two for me was didacticism, and how to engage students about art and education. As an outsider, whose English is a second language, and as a native Arabic speaker learning about the term didactic for the first time in the U.S., I realized that there is no equal translation for the term in both languages. I learned that in Arabic the word “didactics” simply translates to “the art of education” or “ فن التعليم ”. Whereas its use in English is much more complex and layered. This example of the term “didactics”, and its unequal Arabic equivalent, points to the messiness of the foreign experience: the difficult journey of an outsider entering into a new context of critical thinking, who tries to make sense of the local signs and signals, the specific codes and meanings in everything ranging from gestures and words to phrases and discourses.

Ultimately, my thesis for the Masters of Art Education was titled The work is too didactic’: Unspoken Rules Against Didacticism in the Arts & Higher Education. In it, I analyze contemporary phobias around didacticism, the unspoken elephant in the crit room, to contest assumptions, rules, and stigmas in art/making.

AE: What are some of your projects that involve the concept of education?

QA: Within the classroom, I believe in prompting students to reconsider their ideology, assumptions, or parts of their identity that may have been previously unexamined or taken for granted. I engage in critical pedagogy through its intention to address how politics may or may not have constrained an artist’s vision.

I co-taught a class with Asem Naser where we organized a partnership between artists/designers from Palestine organized by the Palestinian Association for Contemporary Art (PACA) and art students at Michigan State University (MSU). Participants worked through different alternative time-based, screen-based processes of imaging in the translation of culture and context, addressing the poignant socio-cultural positionalities of the collaborators in relation to one another. Students worked on several exhibitions, interventions, and publications in the form of postcards and a website they built, named the Unknown.

In the beginning of this collaboration, two defying names were given to the course. In Palestine, it was called: “Non-Geographic, Non-Political Dialogue” and in Michigan: “Critical Geopolitics in Collaborative Practices.” Immediately the desire to make non-political art clashed with the importance of addressing the realities of all the collaborators. The works were created in a liminal space between the two groups entangled within the reality of an occupation. The MSU Global Travel Registry classifies Palestine simply as “Unknown.” Inevitability, this act invents a new set of borders between what is “unknown” and what is acknowledged. This systematic erasure represents this exchange more than either of the course names had initially created.

Another one of my recent projects that dealt with education and artmaking is I Yawn Because You Yawn: Intercorporeal Art as Political Witnessing. This was a commission for the Global Social Witnessing Conference at the Ubiquity University, Germany and it consisted of a collective experience of seeing, listening, writing and drawing for 80-90 minutes, creating tactile and temporal evidence of the five senses.

I faced some censorship during the preparation for this project, and because of that I began to approach it as a 1948 therapy session with a German audience. I was asked by an organizer from the German side: “How can you also hold the perspective of Israel in your work? Especially in Germany, it is important to also bring in the perspective of Israel.”

I included this loaded question within the video collection I created for global witnessing. Through acts of recognition of other presences and existences, explaining archives, memories and a-tonal music from a specific year (1948), we explored the journey to remember and hold on to those histories. Through a global and social-distanced contagious yawn, my question was how might we project that year from a Palestinian perspective onto the German landscape?

AE: You were a 2019-2021 Core Fellow at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Can you tell us more about this program? In what ways has this experience enriched you and your practice?

QA: The Core Fellowship was the first time in my life that I was not teaching and not studying in an academic setting while working as an artist. I would traditionally have had to steal time from teaching or studying in order to create work for my art practice. But in this two-year residency, I was being provided with the time and the space to simply make work and this was such a novel experience for me.

The pandemic broke out at the end of our first year and at the time, the annual Core exhibition was forced to shut down after the opening night. The remainder of the program was completed remotely and instead of our final exhibition, we published a book featuring all the participants’ works. It ended up being an important exercise in collective adaptation.

AE: Many of your works center around different personas that you have or have not encountered and who become the voice of the works. Can you discuss these patterns and encounters within your overall practice?

QA: I have always been fascinated by eccentric or particular people who may be intolerable to others, but to me, can also amuse my sensibilities as they can reflect personal questions and contradictory realities. Encounters with different personas (real or invented) have often been the starting point for my various works.

By speaking through others, reading one location across another, or even by trans-creating one site to another, I try to expose the structural conditions of another location within my work. I use visual translation, substitution, appropriation, and installation strategies to queer forms of imaging, and visual communication architectures. Giving new contexts to the contemporary and historical moment, I seek to blur the past and the present in order to question our political future.

Robert Smithson writes that the non-site can represent the site without resembling it in a metaphoric relationship. I’m not working with representation between sites and non-sites. I’m framing a linkage that is much more fraught in terms of contested geographies. If a metaphor is stating that something/site is like something/site else, then the “like” is the relation. Some of my projects that reflect this are Memoir, Costume Party at the Moslem Temple, and if you Like you can show my works in galleries. To describe one in a bit more detail, in if you Like you can show my works in galleries, the project consisted of reproductions, amended catalogs, lectures, and video that casted me in what Kyle Dancewicz who curated this work in a show at New York’s Sculpture Center in 2020, calls “a one-sided relationship of magnetism and repulsion with a total stranger, playing out a complex, perverse, and somewhat enticing form of misrecognition.” I play between truth and fiction but also deal materially through different indexical processes of copying such as video VHS systems and other components with the untrue narrative installation strategy.

AE: What projects are you currently working on?

QA: Two sides of the same coin, is my most recent research-based project where I am dealing with a real person that existed in the 19th century. I was awarded a grant by the Idea Fund in Houston, TX, for this interdisciplinary art project involving deepfake technologies, and performance that investigates technological, personal, archival, political and religious intersections.

I focus on two historical diaries to connect historically internalized homophobia through Ottoman military killings, and medical imaging failures. I expand my methods of juxtaposing temporalities, queering time, having historical figures in dialogue with contemporary events.

In my recent video, Dawoud, Ya Yonathani, I deal with disidentification, queer embodiment, and queering history through queer temporalities. I embody the words of Palestinian educator and Arab nationalist, Khalil Al Sakakini, in the video, asking: “Am I so desperate, Khalil Al Sakakini, to out your dead body, to drag you out of the closet or the grave?”

QAIS ASSALI ONLINE:

Website: qaisassali.com

Instagram: @qaisassali