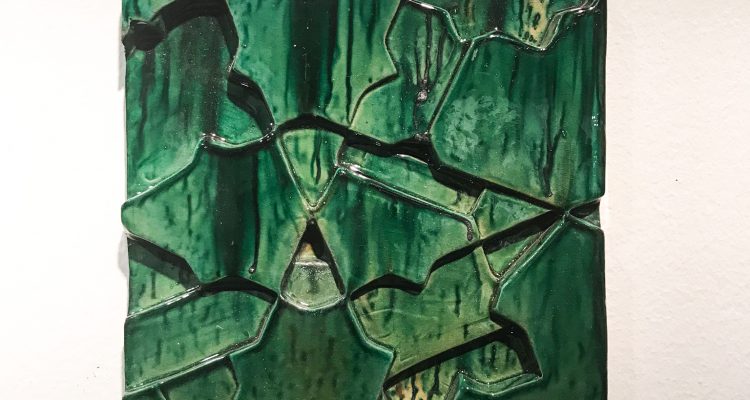

Impression//Impression.Vert #1, 2017, Ceramic and glaze from Tamegroute, Souther Morocco, 20 x 20 cm

Impression//Impression.Vert #1, 2017, Ceramic and glaze from Tamegroute, Souther Morocco, 20 x 20 cm

ArteEast is pleased to present an interview with artist Sara Ouhaddou as part of our Artist Spotlight.

Born in France (1986) to a traditional Moroccan family, Sara Ouhaddou’s work is informed by the experience of growing up between cultures. She began her career as a designer for luxury brands but eventually shifted toward a more artistic and social approach. Her work specifically addresses the diverse challenges facing the artisan community in Morocco, while generally questioning the availability of art as a tool for economic, social and cultural development in the Arab world. At the same time, her characteristic combination of traditional Moroccan art forms with contemporary artistic practices reframes forgotten cultural realities.

Ouhaddou has exhibited her work internationally, including Global Resistance, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France (2020), Manifesta 13 Biennial, Trait-Union, Marseille (2020), Our World is Burning, Palais de Tokyo, Paris (2020) Islamic Art Festival, Sharjah (2017-2018) Crafts Becomes Modern, Bauhaus Dessau Foundation, Germany (2017), Marrakech Biennale, Morocco, (2016) and also had an exhibition of her work at the Moulin d’Art Contemporain Toulon, France (2015), Gaite Lyrique Tanger-Tanger, Paris (2014), and Marrakech French Institute (2014).

ArteEast: Can you tell us about your work in general and the main themes you return to in your practice?

Sara Ouhaddou: My practice is based on collaboration with communities of artisans, mainly in Morocco. The works are the witnesses of our exchanges and our debates on the facts of society, politics, history, etc. The works superimpose the practices according to the subjects that we approach with the craftsmen. I design protocols that always aim to find out how art and culture can be tools of emancipation and development. My practice is the permanent experimentation of tools for economic and social development in specific contexts.

I am obsessed with what I call the right place: a place, a moment, an equal state for everyone but not the same for everyone, always different because it is specific to everyone. Therefore I am fascinated by the idea that somewhere we could all understand each other through systems (of writing, among others) that would be specific to each other. That’s how the signs of the Berber carpet work; a person expresses himself by weaving, and all the different communities can decipher. The history of the alphabet is the history of identities. A civilization that replaces another by destroying its mode of expression and that tries to extend it to the maximum, equalling a smoothing of diversity and a loss of precision. It is the world that is becoming less and less fair. I am looking for ways of writing where nothing is equal, nothing is parallel, and nothing is opposite. It is multidimensional. It allows me to create and, in short, express myself and share my point of view on the world.

AE: You’ve participated in various artist residencies around the world. In 2018, you were a resident at Art Initiative Tokyo, and you traveled across Japan doing research. Can you discuss the series you developed in Japan?

SO: I relate the Jomon period to the Antiquity and Prehistory of the Amazighs in Morocco.

I am interested in the very first systems of comprehension engraved, weaved and drawn present in the hand-made objects of the daily lives of these populations. A direct means of expression specific to a context and therefore singular. A singularity that does not prevent its universality. Between the Japanese of the Jomon period and the Amazighs, there is a very close cultural ground, the signs overlap. I find in each of these people the same way of expression.

A return to a primary expression that comes from the raw state of the human being. A still-virgin state that fascinates me. Indeed, these modes of expression emanate directly from the being. A form of purity emerges from these symbolic expressions. The geographical distance between Japan and Morocco highlights the idea that languages can be universal. And that the human being was capable of being singular while being part of the community.

This makes the modern idea of globalization obsolete. The smoothing of codes, the elimination of differences, of porosities is more and more real. My research in Japan aims to give us the foresight of the past to rethink the transformations of the future.

So as a first emergency, I have developed a body of work called AA, made of four pieces, two are still works in progress. Atlas (1) is a repertoire of forms that are present on Amazigh domestic objects. I traveled across Morocco and asked craftsmen and craftswomen to draw me a sign and give the meaning. This object collects the main forms, and at the same time, it questions the action of how to archive something with written equivalent.This raises the question of the colonization of primitive peoples through writing. Aomori (1) is the same for the Jomon sign from Japan. I just finished it with the Aomori Contemporary Art Centre (ACAC) in 2020.

Atlas (2) is a body of three sculptures made by a marble that is almost four hundred million years old. The marble is made of fossils that used to be on earth before us— with the very first evidence of life. Here I question how human beings always find ways to control their environment to create systems. At the end of the piece, the same shape always repeats itself to be easy to understand by the maximum. I will make Aomori (2) this year.

AE: Can you talk about your installation, I Give You Back What’s Mine / You Give Me Back What’s Yours, which was part of the Manifesta 13 Marseille in 2020?

SO: The installation “Je te rends ce qui m’appartient / Tu me rends ce qui t’appartient” (I return what belongs to me/You return what belongs to you) began over a year ago when I was an artist resident with the French Institute of Morocco and Fræme at the Friche la Belle de Mai in Marseille. I had applied to the residency with a proposal to research the historical traces of a population that was once present in Marseille’s territory. I was looking for the possibility of exchanges between Arab peoples from across the sea and inhabitants of Marseille.

During my research, I went to the Musée d’Histoire de Marseille (a Museum dedicated to the history of Marseille) and found the kiln of Sainte-Barbe in the Middle Ages room. Dating back to the 13th century, this kiln was captioned as “islamic technology” and had been discovered near the city, in the hills of Carmes. It is a testament to the existence of a neighborhood of Arab-Andalusian potters who, for over a century, produced objects for everyday consumption that we still see today. The kiln’s existence, history, and the nature of its placement within the museum, are all points of departures for the project that I developed with Manifesta 13.

I met with the Manifesta team at my Friche studio in the Summer of 2019, after which I became a permanent artist resident at the museum where I could directly conduct research with its conservators. I literally conceived of my work in the museum in consultation with the team that had worked on the dig where the kiln had been retrieved. The elements in my installation are both organic and mineral, and were created from the knowledge exchanged during the Middle Ages between Marseille and the Arab-Andalusian world. The work attests to the erasure of historical records and puts into question current Historical accounts. I even wanted the title of the work to also refer to these exchanges that constantly took place and that finally, were defined by the invention of the kiln. Things are in constant movement; I could have also called the work: “Ne vous inquiétez pas, rien n’appartient à personne, tout est à tout le monde” (Don’t worry, nothing belongs to anyone, everything belongs to everyone). Because ultimately, this is the story of constant exchanges.

In the installation, everything is fake, and everything is real. The story it tells is real. I invented all the actual components that work is made of based on true accounts and by using archeological research methods. The ceramic bones are the fruits of my imagination and a reinterpretation of scientific conventions. By recreating the objects from Saite-Barbe, I give life to the missing necropolis from the original dig that took place in 1997. I want to remind everyone that these objects are man-made.

The blue tables are “mechanisms of choice:” how did researchers analyze, identify and bring things to our attention? Which objects are placed on display, and which ones are placed stored in the archives? What excites me is to reaffirm these emotional dimensions within history and its writing. I want to question the choices of our predecessors.

AE: What and who are some of your greatest influences?

SO: I have no precise idea. I am sort of passionate about so many things. I am curious about every aspect of science, and at the same time, I draw my inspiration from the whole craft universe.

I spend my time reading, visiting, and meeting with every person or practice I can: archeology, history, oceanography or candy makers, etc. On the other hand, I spend the rest of my time meeting with crafts communities everywhere I go—Morocco, France, Japan, etc. I learn from them the most. They are my greatest influence.

As for artistic movements that influence me most, I am not able to say anything particular. The more that I study, read, and watch as many art scenes as I can, I learn that I could spend years into the Memphis movement and then be keen on the Art movement in North Africa between the 50s and 70s, or Frida Kahlo and after that all the women movements of the 60s. I like jumping from design to architecture to contemporary art. I am like a sponge. I am interested in everything equally and keep all that I learn in a corner of my head and one day the connections shall be made.

AE: What are you working on in the studio right now and what are some upcoming projects that you have coming up this year?

SO: At the moment I am spending time working on the final project of my study of similar signs between Japan and Morocco. It will be an installation called “Une conversation banale”, a kind of shaping of my AA manifesto, which I have been building since 2017.

I am starting new research with Art Explora, including a project about Amazigh myths that have never been collected and recognized as the Grec od Egyptian one. Even if they existed before those ones, and they are all linked. I am studying their “filiation” and their representation in the Museums and libraries of the world. North Africa is the birthplace of many myths but is written almost nowhere. If it is written or shown somewhere, I would like to find it! I have no idea what will be the final project, but it’s my new focus. And it’s a big chapter!

I am also working with craft people on a project where we question the future of craft as an archive. I am wondering how I can create a new “portrait ” archive for crafts masters that are rarely represented. It is a project called “Sura”, and I am helped by AFAC for this one.

This year and the upcoming years will be dedicated to those three different research projects.

SARA OUHADDOU ONLINE:

Instagram: @ouhaddou_sara