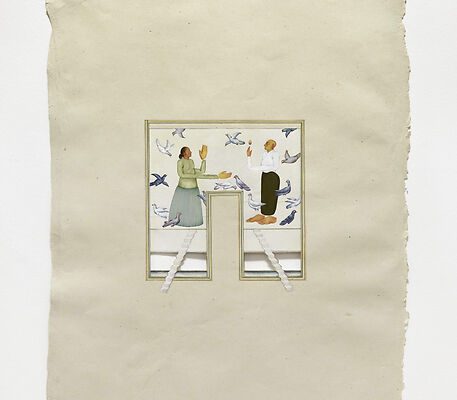

Home, 2020, Natural pigment (including genuine Malachite, Indigo, Lapis Lazuli),

watercolour, 24k gold on handmade Indian hemp paper, 55 x 80 cm

Home, 2020, Natural pigment (including genuine Malachite, Indigo, Lapis Lazuli),

watercolour, 24k gold on handmade Indian hemp paper, 55 x 80 cm

ArteEast is pleased to present an interview with artist Laila Tara H as part of our Artist Spotlight.

Laila Tara H (b.1995, London) is British-born Iranian artist, based between Tehran and London, specializing in contemporary Indo-Persian miniature painting. Raised across the world, she paints largely autobiographical reflections of a life navigating cultures. Having specialized in Persian and Indian Miniature painting during her Masters at The Prince’s School of Traditional Arts, her practice is rooted in traditional methods and materials. Drawing inspiration from the rich history of miniature painting across the Middle East and South Asia, symbolism seeps through her chosen imagery and into her means of making. All paints are hand-made from (semi-precious) mineral, stone, or plant derived pigments and her paper is natural hemp also hand-made in Jaipur. Respect for the cultural and craft elements of traditional miniature painting are inherent to her practice, as an ode to nature and to the dense history that allows her to practice today. Big empty spaces, small intricately detailed additions, telling stories.

ArteEast: What has your practice/career focused on during the past five years?

Laila Tara H: Have you ever been recommended a series to watch by a friend? It starts out agonizingly slow but you’ve already spent months promising you’d start watching. The first few episodes are spent looking more at Instagram and WhatsApp than the actual show until suddenly you’re hooked. You can’t get enough and end up binging an entire series so far in a week. Now you’re sitting there itching for the announcement of the next season.

The past few years have felt a little like that, the chunk of them spend learning slowly – focusing more on the ability to paint than the painting itself. A steady incline of ability, of constant relearning – glorious. My master’s, completed in 2019, was a big part of this, a wholly practical study steeped in traditional craft. Afterwards, it took a little time to translate that into something that felt less redundant, something worth more than the method of its production.

AE: What are you currently working on or considering?

LTH: At the moment I’m working on a body of work for a solo show in Tehran in autumn 2021, expanding my practice outwards from painting to include more sculptural play with materials. Materiality, paper, fabric, carpet weaving, papier-mâché. Indicators of cultural aesthetics, crafts passed down through generations to tell stories and live with. That’s the most important, really, the function of an object not just as a “story teller” but also a thing of warmth that you come home to. These are crafts that travelled: papier-mâché moving from Iran to Samarkand to India, caravans carrying carpets from the Persian empire that eventually ended up in European castles and cathedrals. Home while moving, foreign while resident. That’s my biggest consideration at the moment.

AE: What was your inspiration in pursuing Persian and Indian miniature paintings?

LTH: There’s a story, one that’s only mine and can only be told in a language that feels like my own. I didn’t know that when I started to learn though. All I knew at the beginning of my lessons in Persian and Indian miniature was that I felt liberated from oil painting – from what felt like a European belt pulling tighter with every nude portrait and fruit bowl I was practicing. Miniature painting was so familiar, I’d seen these symbols and colours and textures my whole childhood but had never really considered them as valuable art. Instead, I had spent summers coming to London and walking through big museums with grand historical paintings in oil and believing that was value – that was the worthy work. We’d been taught about the most famous painters in the 14th to 20th centuries. They never included anyone from outside Europe, unless there was talk of “primitive” art forms or in the context of Van Gogh loving a Japan he never visited, Gauguin painting naked girl-children in Tahiti or voyeurs in African and Middle-Eastern bath-houses and harems. The places I saw sights that were vaguely familiar were in The Turkish Bath by Ingres, or anything by Jean-Leon Gerome. What an absolute curse.

The cure only came when I was looking for a master’s, after a bachelor’s in a totally different field – more academic. Here came a focus on traditional arts in the Middle East and it felt serious enough to justify making a permanent move to the arts. I didn’t realise it would allow me to give eurocentrism in painting a middle finger with a big smile drawn on it. It felt so natural to use materials that my ancestors used and to take on a more calm approach to painting – every brushstroke matters and concentration is the winner. While I still fantasise about my “Vicky Cristina Barcelona” moment, where I throw a bucket of paint on the ground and swing my hair around, painting traditionally is a hell of a lot more peaceful.

AE: Do you think this time in quarantine hindered your creativity? Did you find ways to curb this, and continue to grow and develop during this uncertain time?

LTH: Not in the slightest! Without Covid-restrictions I’d still be pining to paint full-time while grasping at every other more “sensible” avenue that came my way. The shutting down of everything brought me focus, it silenced my doubts about whether being an artist was a wise life choice because frankly, there was no other option. The pandemic has been awful for so many and it brings me a huge amount of shame to say this but I have to thank these ‘unforeseen circumstances.’

I was lucky, my studio was my spare bedroom and I lived alone – so the solitude wasn’t a huge shock to my system. There was a sudden determination to paint well, well enough to be able to share the work with pride. Painting became a way to sustain myself, there was no more freelancing or safety of part-time jobs. There was quiet, with the exception of the ice cream truck and a young orthodox MC who drove around the neighbourhood blasting Yiddish music from industrial sized speakers. In a city that was becoming increasingly more surreal, painting was the one thing that felt most simple.

On top of that, I grew up moving around the Global South in places that weren’t safe in the way that London pretended to be. I was, almost luckily, accustomed to staying home and unreliable supermarket shelves. While there was no way of being used to a Covid-19 level pandemic, maladies like malaria, dengue, polio were never far outside our doorsteps. It’s hysterical to think that hand-washing feels like a new thing here, when it was ground into our brains as children.

AE: Nature plays a huge role in your work – the sun in specific is a recurring theme. What aspects of nature inspire you most and do you find that making time to be outdoors enhances your work?

LTH: When you grow up moving constantly, there are constants that you look out for. Mine were nature related. I find stability in the certainty of pigeons and growth. No matter what was going on or where we were, there were always fruit trees in the garden and our weekends were spent buying flowers to plant – irrespective of whether we’d be living with them a year later. Somehow, there was nearly always a papaya tree and rosemary might be the most international shrub.

All of our human things can be falling apart while nature continues its cycle. The most reassuring repetitions: a tree will lose its leaves, little stubs will stick out of its branches, blossoms follow, leaves start lime green, turn deep green, go brown, fall and little stubs will stick out of its branches again. The sky is the same, it doesn’t care – it’s just there.

AE: Could you tell me about the empty spaces in your pieces? The simplicity of this blank space conveys a notion of purity – what is your philosophy behind this?

LTH: My most honest moments were always solitary, growing up and now. Walking along the road outside our house in Tashkent to sneakily pick fruit from the neighbour’s plum tree, siting on the roof in Ankara to breathe. It was sitting quietly in the middle of night on my bedroom patio in Colombo when I really felt myself. This is one of the most phenomenal of lessons; that identity is, really at core, nothingness. It’s not the performative aspect of how you behave or what you wear or how you talk – even what tone you speak with. It’s who and how you are in utter silence and solitude. Everything else is an accessory that makes up how you exist in your context.

That’s the most core reason why. In aesthetic and more practical reasons, the paper is hand-made. It is glorious in its material and its history, a family making paper for generations. It would be an insult for me to use it as nothing but a surface. It also doesn’t need it. I’m a big believer in material as a final object in and of itself – that all I’m doing it accessorising it with my story, with takes of home/heartbreak/intrusion/whatever. It doesn’t need my additions but we’re working together to create something that gives us both space to talk. If that makes little sense, think of the room or the pot in Taoist philosophy – it is only functional when there is empty space and there is purpose in that emptiness.

LAILA TARA H ONLINE:

Website: www.lailatarah.com

Instagram: @llailatarah