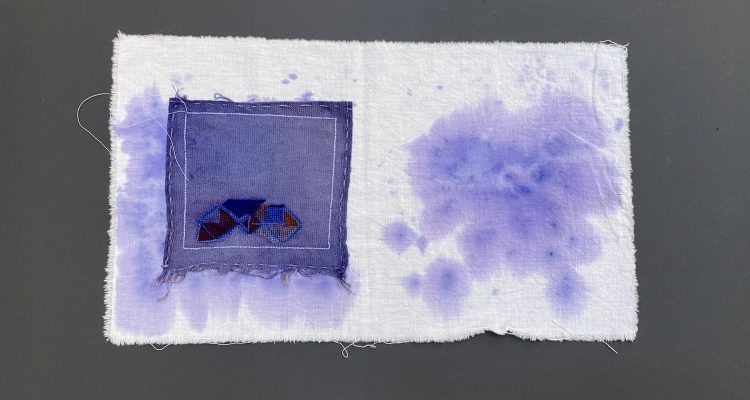

Muscle Memory, experiment (II), 2021, cotton thread on cotton fabric, indigo coloring dye.

Muscle Memory, experiment (II), 2021, cotton thread on cotton fabric, indigo coloring dye.

ArteEast is pleased to present an interview with artist Majd Abdel Hamid as part of our Artist Spotlight series.

Majd Abdel Hamid is a visual artist from Palestine. He was born in Damascus in 1988, and is currently based between Beirut and Ramallah. He graduated from Malmö Art Academy, Sweden (2010) and attended the International Academy of Art in Palestine (2007-2009). Abdel Hamid’s work has been featured in numerous solo and group exhibitions. His solo exhibitions include Majd Abdel Hamid: Muscle Memory, CCA: Center for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow; Majd Abdel Hamid: 800 meters and a corridor, gb agency, Paris (2022); Majd Abdel Hamid, A Stitch in Time, Fondation d’Entreprise Hermès, Brussels curated by Guillaume Desanges in 2021. He has taken part in several international residencies and workshops, including March Project (Sharjah Art Foundation, 2015), Former West (Berlin, Germany, 2013) and Truth is Concrete (Granz, Austria, 2012). Hamid worked in residence at the Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris in 2009. He was a finalist for the Young Artist of the Year Award, presented by the A.M. Qattan Foundation, in 2008, 2010, and 2012.

ArteEast: Can you tell us about your work in general and the main themes you return to in your practice?

Majd Abdel Hamid: A major theme within my work is time and the concept of waiting; I explore the texture of time, memory and trauma, and how to process all this through the intangibility of time. Another important aspect of my practice is how I situate myself in relation to the identities that I have inherited. I question the socially constructed image of those identities and how I deal with a troubling separation anxiety as a coping mechanism, a perpetual trauma, a palpable intergenerational sense of loss, and a nostalgia for inherited memories.

Embroidery is this soft spot that can activate a relatively autonomous narrative. It is an alternative to the fetish of violence and overeagerness to catch the public’s ever-shortening attention span. Reclaiming the practice is a process of reclaiming a sense of normalcy. It is a much-needed connection with locality; an effort not to fall into the trap of national manic episodes or bouts of depression that soon follow.

Embroidery is a way of seeing, working, and abstracting. It is part of a vibrant, expressive heritage that develops, interacts and intersects with life, grief, happiness, anticipation and waiting. This heritage is something that I hope to work with; heritage as a continuum rather than a mummified set of patterns.

AE: How did your relationship with embroidery develop? When did you begin incorporating the technique within your fine art practice?

MAH: The first time I ever experimented with embroidery was during an artist residency at Cité des Arts in Paris (2009). I was in the process of moving to Malmo and spent four months experimenting. My graduation project at Malmo Art Academy ultimately consisted of four embroidered portraits. Then in 2012, I collaborated with a group of women to embroider a “pop-art” portrait of the Tunisian vendor that set himself on fire sparking the Arab Spring for the Young Artist Award by A.M. Qattan Foundation in Ramallah.

It wasn’t until 2015 that I started to develop a practice with embroidery not only as a medium but also as dialogue. I asked a craftswoman to produce a white square, mimicking Malevich’s white square, as I wanted to see it. She refused and said, “son this is a waste of time.” And this was precisely what I wanted to do: to record time, wasted time, by doing a repetitive gesture of filling the canvas with white cross stitches sans patterns, symbols, or imagery, simply stitches and the amount of time it took me to finish each piece. At the same time, I started working on the series Screenshots after watching hundreds of videos from the uprising in Syria (2011). I began taking screenshots of the spectacle of violence that our eyes became desensitized towards and then embroidered them. It was also an investigation into a flat pixelated image that could be transformed into textured fabric. Ever since, I have always kept a piece of white embroidery close by; it has become a daily ritual of de-accelerating and contextualizing.

AE: You recently opened a show in September at CCA in Glasgow entitled Muscle Memory. What was the concept behind this project and tell about the themes of grief and ritual that you explore.

MAH: This work is an attempt at reclaiming a practice. I want to reconcile a relationship with a city and claim a small repair space: not as a reaction to disasters but as a continuum of interaction, openness, and reflection. Ultimately, the practice of embroidery as a responsive medium is fragile and borderline neurotic.

There is a lingering question on how to mourn for a city. In 2019, an uprising brought life to the city of Beirut. In retrospect, it feels as though it were a farewell collective action. The economy collapsed and hyperinflation was a slow cruel death: “value” changed every day, everyone’s savings evaporated, and soon even the public lights were turned off. The city seemed almost unrecognizable, broken, and profoundly debilitated. What to do then? It was unavoidable. Is it possible to grieve and allow another relationship with the city to grow, unhindered by nostalgia and projection?

A story about a mourning tradition has lingered in my head since I learned about it. Among some Palestinian communities, a handmade dress is drenched in indigo as a visual testament of bereavement. In the beginning, the dress is rendered completely dark by the dye, but as it is washed over time, its color starts to reappear, making for a very poetic, performative grief. Muscle Memory is an intuitive attempt to transform the experience of color, lines, and geometry into a motif that is then repeated until a pattern emerges. The motif is embroidered on three pieces of cloth: a cotton sheet, pajamas, and a towel. The pieces are drenched in indigo dye and scrubbed using soap and a toothbrush until some colors reappear.

AE: Immediately after your opening in Glasgow, you had an opening at gb agency in Paris entitled 800 meters and a corridor. What does the title signify? Tell us about this new body of work and this project relate to your current practice.

MAH: This project came as a result of a hypothetical answer to the question: how long was the thread that was used to stitch people up after the seismic explosion in the Port of Beirut in august 2020?

I genuinely resisted working on it, because there has been an over saturation of imagery, and a problematic relationship with catastrophes. But there is also the question of the urgency to work.

Ever since I moved to Beirut, I enjoyed a sense of autonomy, a subjective one of course, commuting between carefully constructed bubbles. But once the explosion happened, I was suddenly part of a community. It was not about accepting it or not, there was no choice to be made and that didn’t change the fact of the matter. How do you deal with this? Suddenly you no longer have a disconnected existence, working through insomnia. It becomes very personal, and in a way, there is a thread, a thread of stitches. Thread, because most people were injured by shredded glass and received stitches to close their open wounds.

This then, was the starting point: to try and hypothetically calculate the length of this thread, that is 800 meters, if we on average calculate 10 cm of thread for every registered injury (about 8000).

I got threads that cumulatively measured 800 meters and started weaving, unweaving, cutting, and finally, sewing these pieces to other fabrics that I already had in my possession (table cloths, napkins, pillowcases).

The corridor is a start of a new project that deals with safe spaces. I have been asking people to draw a map of their homes and to identify the safest spot (if they even have one). It is quite interesting for me to map the topography of safety within the home, and I’m looking forward to the many intersecting layers that this project might open up.

AE: Tell us about your ongoing series, Son, this is a waste of time. How did it come about and what about this project is ongoing?

MAH: I am quite fascinated with the Suprematism movement. I have been thinking about what if embroidery also becomes a formal artistic movement, what would that look and feel like?

In 2015, my first impulse to get a perfectly done embroidered white square was by commissioning a professional embroiderer who refused. She told me, “Son, this is a waste of time.” I respected that, yet began doing it myself. It proved to be painstakingly long, yet quite enjoyable. I must also admit that I have become much quicker than in my early pieces. Still, whenever I have these fragments of time, spent either waiting, watching the news, insomniac, or obsessing about a new story, I have made it a habit to keep a square embroidery on hand. It has proved to be quite interesting; I am usually restless, but this repetitive gesture is both soothing and opens up a space to think beyond dualities and dichotomies.

AE: What and who are some of your major creative influences, and why?

MAH: I find “accidental art” fascinating and this urgency to do something so that one does not lose their mind is very inspiring. One example of this is craftsmanship in prisons where it becomes an intense way to deal with deformed time. Riad Al Turk is a Syrian dissident who spent 17 years in solitary confinement. He started using lentils that he collected from soup to draw patterns on his bedsheets and he would remove then at the end of the day to start anew the following morning. He says in an interview with filmmaker Mohammad Ali Atassi that this was his way of not giving up or losing his mind; preventing himself from thinking, and to eliminate daydreaming.

Another inspiration is an obsessive-compulsion with the mundane. I pay a lot of attention to details and I am fascinated by how people cope with traumas. Each space or city has its neurotic tendencies; one needs to spend a proper amount of time and be genuinely present in order to experience, engage with, and find beauty in the ordinary.

AE: What are you currently working on and do you have any shows or projects upcoming in 2022-2023?

MAH: Currently, as I have just returned to Beirut following two back to back solo shows, I think a break is due (even though I am not sure what to do on a break). Regardless, that is the plan for the next few weeks, to rest. The project about safe spaces is an ongoing one that I plan on exploring more in the coming months, alongside a bit of reading and of course, white embroideries.

MAJD ABDEL HAMID ONLINE

Website: Majdabdelhamid.com

Instagram: @majdabdelhamid