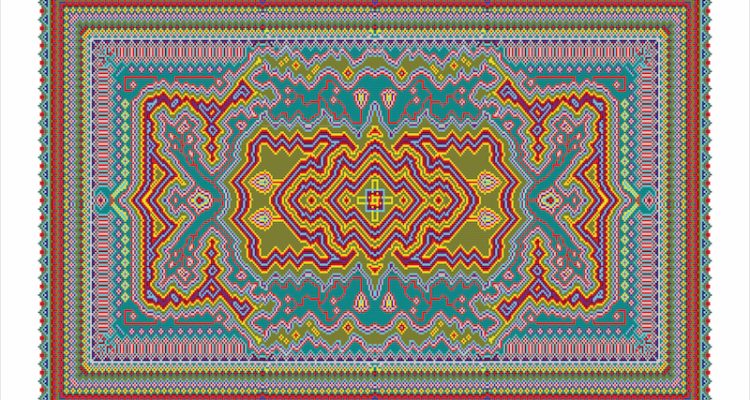

MBTC N1, 2018, Produced in Microsoft Word, Digital Print on Watercolour Paper, 44 x 66 in

MBTC N1, 2018, Produced in Microsoft Word, Digital Print on Watercolour Paper, 44 x 66 in

ArteEast is pleased to present an interview with artist Shaheer Zazai as part of our Artist Spotlight series.

Afghan-Canadian artist Shaheer Zazai is a painter and digital media artist. His practice focuses on exploring and attempting to investigate the development of cultural identity in the present geopolitical climate and diaspora. He received his BFA from OCAD University in 2011 and was the OCAD University Digital Painting Atelier Artist-in-Residence in 2015, where he produced his first Digital Carpet. Zazai has exhibited his work in solo and group exhibitions including at the Aga Khan Museum, Toronto, ON; Owens Art Gallery, Sackville, NB; DARC Project Space, Ottawa, ON; Patel Brown Gallery, Toronto, QC; Centre de Design at UQAM, Montreal, QC; Centre[3] for Artistic + Social Practice, Hamilton, ON; and A Space Gallery, Toronto, ON.

ArteEast: Can you tell us about your work in general and the main themes you return to in your practice?

Shaheer Zazai: I have an active studio practice in painting and digital works that I have presented in the form of print media, textiles, installation and forthcoming public art projects.

In a very broad way, my work is an exploration into the development of cultural identity in the present geopolitical climate and diaspora. zthe more I work in the studio and switch between mediums, a lot of sub branches emerge.

I am curious about how we respond to rules, boundaries, limits, and consequently who we become because of having to navigate these prescribed conditions.

AE: How did you begin creating carpets and in what ways does this constitute a digital practice?

SZ: I consider it a digital practice because everything I am creating is rooted from a digital medium and in my case, the medium is a word processing software through which I create visuals that resemble and mimic textile patterns.

I started creating carpets digitally using Microsoft Word. This whole project was not intended to become an art practice. I am and was a painter prior to this digital direction in my studio practice. It was January 1, 2013; a year was culminating while another beginning, and I had found myself perpetually sitting on a couch with a deep sense of idleness and unfulfillment. As a form of self punishment for spending too much time on the couch in front of my laptop, I challenged myself to type 2013 dots on a Microsoft Word document. The challenge was to not get distracted or give up–I thought 2013 dots and spaces will be very difficult and I was surprised when I had completed it effortlessly. From this point on, my drive for experimentation kicked in. MS Word has 15 highlighter colors and I assigned them numerical locations on the page and started placing them accordingly. By playing with numbers, colors, and repetition, I was able to form patterns that resembled those found in textiles.

The emergence of textile patterns created an internal conflict for me, as I wasn’t a textile artist to begin wit. It was as though I did not believe I was allowed to create textile works. The more I attempted to make the digital design non-textile-like, the more they resembled textiles. As I continued experimenting, I would test new rules with each new work. For example, I was only allowed to use the numbers 3, 4, 7 and only to use the colors dark blue, teal, and gray. I was making anywhere between 1 to 3 small pieces a day. Back then, I was like a child playing and testing rules of a new toy that I had just found. I was not aware of much of what I know about my practice and process today.

The concept of creating actual carpets with a Word document was initiated when I applied for a residency at OCAD University called Digital Painting Atelier. By this time, I had come to terms with the textile direction that the medium (MS Word) wanted to take. What I also realized was that my process of playing with numbers actually had a direct relationship with textiles. Textiles are a series of numerical decisions. Every shape, motif and design in a textile is created using a set of mathematical combinations of knots, stitches, or woven intersections. In carpet terms, how many knots does it take to create a flower, a petal, a stem, etc…? One of the elements that defines the value of a carpet is its knot count. The denser the knots per square inch, the higher the value. The bigger the pixel count, the higher the digital quality of an image. The thread count of a fabric tells us the quality; the resolution of an image tells us the quality. For my work in MS word, this was a decision to determine how many characters I typed, how many I highlighted, and in what order.

I applied to the residency with the intention of creating the first life size carpet design using MS Word. At this stage, I learned that carpet designs are in fact garden designs. Just like a garden has walls and boundaries, a carpet has a border design that acts as the frame of the carpet. A garden has a central fountain from which water channels branch out and the rest of the garden gets curated around it. In carpets, there is a central motif, and sometimes multiple central motifs, that each have subsequent patterns that form around it.

At the residency I created the digital piece Zarghoon Carpet. The garden became the rules for this digital carpet: I used boundaries, a central motif and everything else formed around it. The other rule for this piece was that the residency was one week long, and I had to take one week off from work which equaled approximately 40 hours – so I had 40 hours of typing and highlighting ahead of me. The rest was up to what would happen when I started working. Each shape that was entered into the page defined the rules of the other shapes that would come after. With each shape entered, the empty shape around it changed and this limited what sort of shape could sit next to it.

I often describe my process as the surrealist drawing technique of Exquisite Corpse drawing mixed with Tetris. I am Tetris-ing shapes together while troubleshooting my limits as I work through the page. I don’t know what the outcomes will be, and this is what drives me to continue testing and experimenting.

Today, I feel as though I have gone from the child that was playing with the new toy to an adult playing a mad scientist. All that to say, I began creating digital carpets to address my need for a sense of achievement and along the way I discovered my relationship to limits, boundaries and challenges. I also learned about the relationships between computers, digital image making and textile design. Our relationship with textiles is defined by the mathematical qualities of a textile. They all speak the same language of mathematics.

AE: Can you tell us about the process behind the production of your carpets which also involves a creative dialogue with the weavers? How has this dialogue affected you and your relationship to your culture?

SZ: The carpets were produced by a group of Afghan women in Afghanistan. The journey to getting the carpets made in Afghanistan also began when I created the first life size digital carpet Zarghoon Carpet.

Since creating the first digital carpet, I had wanted to turn them into hand-made carpets that would be produced in Afghanistan by Afghan hands; textile that were coming from that air and land. I started asking around to see how I would go about getting this done but the responses I got were all directing me to produce them in Iran, Pakistan or India–anywhere but Afghanistan. One of the carpet sellers I was talking with told me that they could get carpets from Afghanistan but will come with a tag saying, “Made in Pakistan.” This is because the carpets produced in Afghanistan get exported through Pakistan or they are produced by refugees in camps in Pakistan.

I paused my search for weavers because I wasn’t willing to get the carpets made if they didn’t fit my criteria of being made by Afghan hands in Afghanistan. I was not even until this moment that I realized that my criteria for how and where the carpets had to be made became another rule within the work, this time designated for the physical carpets, and this resulted in obstacles that I had to troubleshoot in order to obtain the final outcome.

In 2020, I was speaking with a family friend about my search for Afghan weavers in Afghanistan and he was able to connect me to someone in Kabul. I sent JPEGS of my digital carpets (12 images) and asked if they were able to produce them in a specified dimension and if they could achieve the colors as accurately as possible. Outside of these parameters, I left the rest to the weavers. After several months I checked in to see if they had any updates for me and I received a few photos showing the carpets. They were real. They were being made in Afghanistan, in that air and on that land. The images I received were low-res and I had to hold my breath till I got to see them in person.

The first time I saw the carpets, I was awestruck, and I still am each time I see them. The quality, the vibrancy, and the liveliness of each digital design has come to life. It is almost like the gardens in the digital carpets have come to life by the hands of the Afghan women that wove them.

Something that amazed me was discovering the creative agency the weavers had taken to modify, adjust and interpret my designs. Where there was a diamond shape in the design, for example, they had replaced it with flowers in the carpets. The more I looked, the more it was evident that these were not mere reproductions of my designs but that they were translations of them. I first displayed them at Patel Brown Gallery in Toronto, and the title of the exhibition was thus, A Call Home. I called the exhibition A Call Home (2022) because I see the carpets as messages from home. Afghanistan has always felt like an inaccessible home. The digital carpets became a message I sent home, and the response I received was the hand-made carpets that are now like manuscripts to decipher.

I really hope whoever is reading this gets a chance to see the carpets in person, to touch them, to hear them. At first glance they are like their digital counterparts but upon closer look, you will find that no detail is exactly how it is digitally. Every single detail is adjusted in some way. In some places the order of colors is adjusted, in other places the detail has been minimized, and in others, simple shapes have been transformed into complex patterns. The human hand is present in every knot of each carpet down to its fringes.

One of the carpets, FLSC40H1W, has a single red flower knotted in it. This red flower is not in my design, and neither is it anywhere else on the carpet. It’s almost like the weaver has signed the carpet. It is so intentionally placed that it can’t be confused for a mistake. Its placement and spacing in relation to the other shapes around it, its resemblance to the other flowers woven in the carpet, the difference in color to the other flowers, everything is evidently a decision made to place the single red flower into the carpet. This red flower is my favorite discovery in the carpets.

AE:How has your painting practice evolved and intersected within your digital practice?

SZ: Prior to my digital practice, my paintings were focused on Afghanistan from a place of rejection. Afghanistan stood as a symbol of failure to me. Through my paintings I wanted to speak about Afghanistan and its failed history, to further illustrate the failure of patriarchy. My paintings were not coming from a position of inviting the audience into a conversation but rather, of wanting to talk at the audience about the negativity that was felt in relation to the identity associated with Afghanistan.

A few years after my digital practice started, I realized that the way my paintings were evolving in addition to the fact that my lens had also transformed from a negative outlook to a curious and explorative relationship with my cultural identity. My digital practice had taken on the burden of addressing my cultural identity crisis and my paintings found freedom from many of its hindering attributes.

In painting, the first brush strokes have always been the most enjoyable moments of the process. They are immediate, honest, energetic, and soothing. Everything following the first brush strokes felt like a chore; I had to render the faces, the figures, the scenes, and illustrate the story. I came to the paintings with a plan to address something specific and render the picture I had in mind. The pictures were referential images of Afghanistan researched in advance and this was too embedded within an academic state of mind.

I chose to approach the next body of work initially with those first brush strokes in mind and to allow my hand to paint what it naturally wanted. I wanted to paint without knowing what the image was going to become and I have been painting like this for the past 5 years. The digital works served as a therapeutic process and the painter in me found freedom. Over the past 5 years, this freedom has transformed my paintings and formed a picture that I didn’t see coming.

Recently I recognised what was surfacing in my paintings. While I was working on creating gardens in my digital works and feeding into my need for structure and control, my paintings were giving birth to untamed garden scenes and abstracted foliage form which a figure was appearing. I have been painting a gardener, a struggling and vulnerable gardener. Yet this gardener, a bearded male figure imbued within an enveloping scene of nature and flowers, isn’t the hero of the story.

I am curious about this figure now and I want to uncover his vulnerabilities. In the digital works the gardens are domesticated, in the paintings however, the figure must answer to the untameable might of nature and face its own vulnerability. I am very excited for what will be coming next in my painting. At the same time, I am very scared of the fact that I have already seen what the paintings have become since I generally prefer not knowing the outcomes of images.

Then again, the evolutions of my practice that I am now sharing, from my digital works and their transformation into carpets, to the development and the changes in my painting, have helped me realize that I am in fact curious of what new discoveries lie ahead.

AE: What and who are some of your major creative influences, and why?

SZ: When I think about creative influences, I think about the encouragement I have received over the years. The drive to creativity has been there as far back as I can remember, but what has kept this creativity alive is the constant encouragement. Growing up my parents encouraged me, as did my schoolteachers and university professors. My dad would bring colored pencils and other art supplies home, and this kind of encouraging support kept me going.

Another influence was my mother’s uncle growing up. My parents would sit with him and discuss history and literature. He used to make miniature watercolor landscapes in his notebooks. All the scenes looked the same and he taught me how to paint them. A mountain range, a body of water and some cypress trees. He was the Bob Ross of my childhood. Today, I know that he was painting Afghanistan and his memories of it.

Outside of these personal influences, figures in art history have only served as evidence that art was not something limited to a child’s play and the need to create is a reality to be pursued.

Today my influences are no different than when they were when I was a child playing around with colored pencils on a page. Come to think of it, I am influenced by the act of art making because it creates the opportunity to be a child and play. Perhaps I am just trying to be a child after all.

AE: What are you currently working on and do you have any shows or projects upcoming in 2023-2024?

SZ: I currently feel like I am an administrative assistant to myself–one of the many hats we must wear in the real world in the pursuit of becoming an artist. Outside of mostly admin and logistical planning, I am currently part of two exhibitions in Toronto: Afghanistan my Love, at the Aga Khan Museum and Ornamental Gestures at Doris McCarthy Gallery.

I also have a video work that I created for Emily Carr University’s Digital Screen Public Art Program. The video work will be installed in Vancouver and unveiled in early March 2023. For anyone in Vancouver, watch out for some public programming around this i.e., artist talks etc.

Simultaneously, I am working on two public art projects, one in Toronto and the other in Edmonton, both projects are in very early stages so I am not able to share much now but do keep an eye out for more updates. These will likely get unveiled in 2024/25.

Finally, I am working towards a solo exhibition in Montreal with Patel Brown Gallery in September 2023.

SHAHEER ZAZAI ONLINE:

Website: shaheerzazai.com

Instagram: @szazai._