This 1999 text was first published by ArteEast in Insights into Syrian Cinema: Essays and conversations with contemporary filmmakers. Ed. Rasha Salti. New York: ArteEast : AIC Film Editions/Rattapallax Press, 2006. 149-163.

Prologue

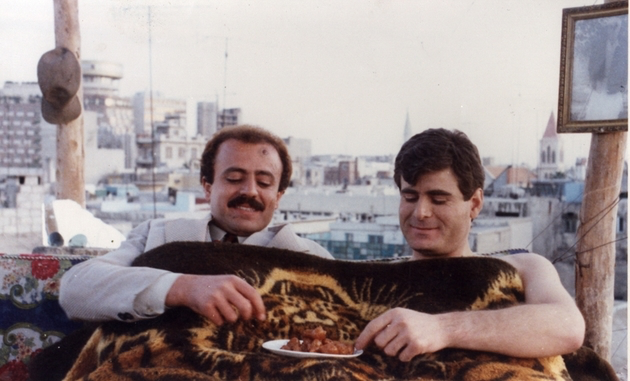

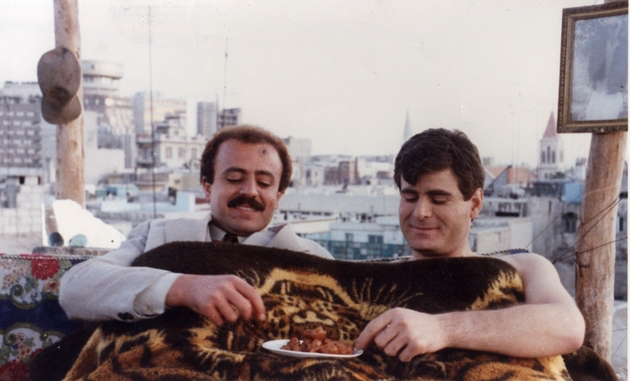

I stood on a street in Paris, dialing Syria from a public phone to share the happy news with my family that my first film, Nujum al-Nahar (Stars in Broad Daylight) was accepted at the Cannes Film Festival. They sobbed, laughed and cheered and announced the birth of Leila, a daughter to my sister Amal. The year was 1988. Until now, I have not made a second film1, but one night, when she was eight years old, before turning the lights out and going to sleep, Leila babbled: “As long as the veto is in effect, what is this democracy are you talking about?”2

Everything resembles everything else, coffee is tea and tea is coffee. The television is there, facing you; the television set, your entire universe. Your least bitter choice from betwixt bitter predicaments, the showcase duel between a sword and a Tomahawk cruise missile, the herald of the decadence of our century.

I pledge not to do unto you as you have done unto us (for too long now), in your American crime and detective films, where the identity of the murderer remains a secret until the last minute. Neither will I follow the rules of the noir of real life, where the identity of the murderer is clear from the first moment, and you spend your life waiting, as one waits for destiny, judgement, tyranny, or globalization, for him or her to fall into the trap. Instead, I will allow myself to propose an arithmetic riddle so we embark as equals on this collective journey —be it Noah’s Arc or the Titanic— and so as to level the ground for communication so we would not require subtitles. And by the way, you ought to be informed that whoever solves the riddle will be awarded with marrying the princess.

In a faraway, beautiful, somnolent country called Syria, early one morning, in the year 1963, a messenger (blowing a horn) announced the enactment of “Legislative Decree Number 258 of the Year 1963” (please imagine a musical interlude here). He blew his horn twice (in fact) and proclaimed: “A public institution has been established, it shall be known as the National Film Organization; it shall be bound to the Ministry of Culture and National Guidance but shall have its own operational, administrative and financial sovereignty; its seat shall be in the city of Damascus. Its objectives are: firstly, to develop the film industry in Syria; secondly, to support healthy production in the private sector; thirdly, to foster documentary and fiction films that will raise the standards of cultural and artistic appreciation amongst the people.”

And here we are on this Wednesday, morning or evening, of the year 1999, gath- ered to discuss cinema in Syria, in a country known as the United States of America that preaches its own new gospel and punishes the unbelieving heathens that don’t endorse it.

To this day, the single agency producing cinema exclusively in Syria is the National Film Organization. Everything mirrors itself and what surrounds it: the single pole, the single party, the single producer, the single film. This is the endgame: the single film production agency produces the equivalent of a single film every single year. Ventures in the private sector evaporated soon enough, their evanescent vapors wafted to the sector of television production. They are all giddy over there now, peeping at strip-tease and lap- dances, smitten with the pretenses of television, purportedly enraptured.

The private sector seems to have expired its last sigh, without sorrow over its years of youth, or its intellectual and artistic contributions. It spent stubborn years waddling to produce bad copies of commercial Egyptian films, which in their turn, were bad copies of American commercial films. Before the angel of death misunderstands me, and for the angel on my right shoulder not to misquote my words, I hasten to correct the record. I am a staunch believer in freedom and plurality, and regardless of their artistic worth, I am absolutely not an advocate of the annihilation of the private sector, nor did I rejoice when it ended. Plurality, diversity, remain until this fine hour, sacred values I endorse whole- heartedly.

But let’s go back to the single film produced in a single year, and a thirty-six year old National Film Organization, pacing slowly, step after step (a single step every year), as if afflicted with plegia from childhood. Our (mother) state granted itself the guardianship of cinema under its mercy, without mercy. It drew cinema into the realm of public administration, and informed by deep lack of experience and foresight it pushed the National Film Organization to fend for itself on its own, and decreed it ought to generate its own financial resources. Thus were the very precepts proclaimed in the infamous decree that marked the birth of the organization and ignored entirely. The National Film Organization and the cultural value of film production eerily transformed to a commodity, subservient to the market and the whims of supply and-demand. This happened under the aegis of state boastful of its socialist creed that admonished the demons of capitalism and the evils of the market.

From its birth, the National Film Organization was bound by labyrinthine laws and codes of the Ministry of Finance and the Commission for Censorship and Inspection that regulate inbound and outbound blood flow for all public institutions, the General Establishment for Meat, the General Establishment for Fruits and Vegetables, and the National Film Organization. The sequence of this previous sentence, draws the full tableau, a still life, or nature morte: meat, fruits, vegetables, cinema. An agreeable ornament to enliven the walls of a living room. In Arabic, nature morte is usually translated as mute nature. Youssef Abdelké, the Syrian printmaker, preferred to call it “nature in waiting.” I am more keen on “nature in somnolence”.

Nature morte has all the evocations of death, murder and crime, and reminds of the riddle I promised to deliver in the preface. The page-long exposé of fact and information that deferred its delivery was unavoidable. I am not a Cartesian, but for the sake of making sense now, ladies and gentlemen, here is the riddle! (I mentioned the reward earlier, but I need to specify that according to the rule, whoever fails to marry the princess will be decapitated. The rule is the same, everywhere and under the rule of every democracy, everyday until today, in some place in this world, a head is decapitated. In some place or other, like Iraq or Palestine.)

And here, Ladies and Gentlemen, is the arithmetic riddle: If the single film producing establishment in Syria produces no more than a single film per year, and if the number of film directors in the employ of this organization is no less than thirty, then, according to the principle of equal opportunities, how many films can one director make in his lifetime? Well, the answer is: one film every thirty years. If given an early chance, the filmmaker would be thirty years old when making his first film, and for the second, he would be sixty years old, obviously, ninety for the third.

Simple enough. Now take me for example (a specimen from Syria who, for reasons of grave importance, does not wish to enlist to an American think tank), and suppose that I wanted to wait until my seventh film to transcribe my autobiography, like Frederico Fellini in Eight and the Half, or Elia Kazan in The Arrangement. A fair estimate to assume that by my seventh film I would have achieved the required maturity of emotional intelligence and depth of insight to tell my story. According to the arithmetic equation just laid out before you, I would have to be 242 years old.

And thus, you will see now, how Syrian cinema holds within itself the essential ingredients of science fiction and fantasy, because 242 is also the number of the UN Security Council resolution that has yet to be implemented. From the lack of implementation of resolution 242, follows the implementation of the Emergency Laws. (There is no riddle. Life itself is the riddle.)

Is Israel alone to be held responsible for the Emergency Laws?

The Emergency Laws don’t recognize the full meaning of freedom because we are in a moment of confrontation, and our land is occupied. They also don’t recognize the primacy of cinema, nor its importance, because we are in a state of emergency. And land comes first. If Israel were to pull out of the Golan in 242 days and demand compensations for dismantling the settlements, we, the filmmakers of Syria would squarely demand compensation from Israel in our turn for the three hundred films that were never produced because their funding had to be diverted to the country’s defense. At least the first third of that total amount. The second third of the figure was absorbed by the Emergency Laws themselves, at a speed faster than a Mercedes 242. As for the third third of that figure (or the equivalent of the cost of a hundred Syrian films), it can only be accounted for by the American veto on the implementation of UN resolution 242, which only served to prolong the life of the riddle.

Obviously, I did not come here to challenge you with a riddle, knowing all too well it has no resolution. Most of the thirty filmmakers have long deserted the camera and eloped, looking to fend for a living elsewhere. Some work as carpenters, others as marketing consultants, advertising film directors, and others have been granted a “green card” to dwell in the land of television where job opportunities multiply at a rate faster than population growth. Only a few of us stayed where we are, doing what we do, like a band of quixotic musketeers at the service of Her Majesty, Queen Cinema.

And everything resembles everything else. We have become the legacy of cinema, with our films, our sounds, our images. We are like the song that the prisoner in Cell Number Six sings, “Oh Hassan! I brought you up when you were a child, why do you deny me?”

Everything resembles everything else, tea is coffee and coffee is tea in this long nightmare (it will become clearer to you after this brief commercial break).

I once ventured into one of the al-Kindi movie theaters (they are owned and managed by the National Film Organization) to see for myself how Syrians experience Syrian cinema, how they read the signs, the meanings. I walked into the theater, and in the space between the front door and the screening room, Abou Walid greeted me. He sat behind a counter, where he had placed a small television set. Despite the fact that it had earned some golden European award, the film did not attract more than ten spectators. They were lost in the room. When the film sequences that I cherished most (and considered vanguard) unfurled and I began to unwind in the darkness, I suddenly took notice of the sound. It was not the sound of the film, nor was it the voices of the actors. It was the sound of the television set near the front door, the sound of the serial. It occurred to me that the physical presence of the sound of the television serial was at par with the physical manifestation of image and sound on the large film screen. Unencumbered from allegorical significance (or not), the sound from the television serial had latched itself onto the large screen, merged with the sound of the film, supplanted it, dubbed it, garbled it.

Sound and image are distinct, but everything resembles everything else; the room resembled a screening room and yet it was not that, the dialogue resembled a dialogue and yet it was not that. I confess that for a few minutes I was mystified by the eeriness, but soon I realized I was enjoying an aberration and betraying a principle, so I sprang up from my seat in the direction of the entrance hall where Abu Walid was absorbed watching the television serial. From behind the glass window of the box office, the television beamed images, whose hybrid aesthetics were intended for fast digestion, and a sound whose reach prevailed over the film inside the screening room. I coughed to get the man’s attention and with one intent stare I held him responsible for marginalizing culture. Out of my keen commitment to pluralism and democracy, I urged him to lower the volume on his television set.

The following day I found myself mulling over the incident and its significance. The day after, I was given more reasons to ponder. Pasted on the wall, at the entrance to the al-Kindi theater, as well as at the entrance to the National Film Organization, a notice of death announced the passing of Abu Walid after a sudden heart attack. He was forty-three years old, exactly my age then. Abu Walid had first worked at the National Film Organization as the coffee server, but after he was deemed to have failed the expectations of that function, he was dismissed and assigned with the lesser task of tearing filmgoers’ tickets at the door of the state-run al-Kindi theater. Because spectators were scarce and ticket holders even fewer, he had installed the black and white television set in the entrance hall to assuage his loneliness.

Abu Walid had failed as the coffee server because he attempted to embody the persona of the late coffee server Abu Badr, the jovial elderly man who was loved by all. Abu Badr noted down everyone’s orders, from the bottom of the hierarchy to its top, nodding his head knowingly and invariably returned with tea instead of coffee. If anyone protested, he retorted first with an affectionate smile that grew into a childlike giggle. He placed the tea down and demured ever so sweetly(even to the director): “Tea is better.”

He said: “Everything is the same”, and continued. laughing, “the only difference between an Arab and a foreigner is coffee.” He said it knowing all too well it would be the occasion to choose tea over coffee, television over cinema, habit over love.

As spectators were individuals, he disregarded their rights and took license to raise the volume of the sound.

Abu Walid tried to resurrect Abu Badr’s voice, he cracked jokes but flopped. The sound did not conform to the image, so… he died. Should there be a causal relationship? He died, and after I read the notice and climbed the stairs of the building, a voice whispered in my ears that donations for his family were being collected, that some had given money and others not. (Here I am reminded of a Russian joke I heard during my schooldays in Moscow. One day, Ivan (then a Soviet) took his television set for repair to another Ivan. The second Ivan asked: “What is wrong with it?” “The sound does not conform to the image, ” answered the first Ivan. “And you expect me to repair the whole of the Soviet Union?!” the second Ivan replied.)

Neither does our own image conform with our sounds-voices, we, the handful of Syrian filmmakers. We were quelled by the routine of everyday life. When questions press us in the media we are jolted into awakening and answer in our idiom of allegories and metaphors. In reality however, we are absent from the screen. And there is no longer a screen, in fact not in allegory, there is no longer a large white screen, no image, no sound, no comfortable seats and no toilets. In the nation’s capital, Damascus, there are only eight movie theaters serving six million citizens, in the city of Homs, there are three, two of which have been under renovation for decades, in Lattakia four movie theaters are still operational as compared to the total eleven, when I was eleven years old.

In 1969, the horn-blowing messenger that announced the establishment of the National Film Organization manifested himself once again. He read a new decree that bestowed the role of import and distribution of films in the country exclusively to the state through its expert appendage, the National Film Organization. As recently as this past March, on the occasion of the celebration of the anniversary of the revolution, the daily al-Thawra reminded us of the wisdom behind these edicts, namely, that many films conveyed ideas antithetical and hostile to the principles of our revolution.

Even if such actions were animated by good intentions, and regardless of the fact that coerced guidance underlines an implicit mistrust of people’s ability to draw judgements on their own and without mentorship, the National Film Organization’s good intentions did not save it from endemic and sustained poverty. It was never afforded the means to import the best or the most contemporary of world cinema, nor was it able to foster a culture of appreciation of cinema. Its monopoly over access was dwarfed by television and the informal traffic of video cassettes. They invaded the “well-guarded” homes and consciousness of people with seamless efficiency. The cherished tenets of our revolution’s ideology were thus defeated by poverty, and the bright image of the Tomahawk, centered in frames unfolding on television sets, beamed into our people’s households. Nor was the National Film Organization able to rival Beirut, only a shy few kilometers away, where film releases are apace with the rest of the world, movie theaters multiply steadily and people don agreeable attire to watch films. It is almost as if the messenger who proclaimed the state’s decrees had blown nefarious winds of a looming tempest from his horn, rather than the National Film Organization’s good intentions, and inspired spectators and films to forsake movie theaters. And we woke up one day to find deserted movie theaters void of lifeblood, rotting in decay, hollowed of their guts. This is not an allegorical image, movie theaters had to dismantle and discard half their seats to lighten the burden of taxation because they are tabulated according to the number of seats, not spectators in attendance. The eight surviving movie theaters in Damascus are now in deep comatose slumber. No radical surgery, heart or spinal transplant can save them, they have been declared clinically dead, at least for the time being.

We are absent from the screen. We are absent from consciousness, from the social consciousness that hungers for freedom, from people’s collective memory, distant or near. The word “film” is never hinged with the attribute Syrian in collective awareness, there is no place for Syrian cinema in people’s collective memory. The notion of a living, breathing, contemporary Syrian cinema registers so much like an aberration that it is perceived to elude the laws that regulate the nation’s everyday life, like the succession of seasons, increasing cost of living, spread of corruption and suffusion of fear. All the things that comprise the cadence of people’s consciousness of living in this country.

The single film produced every year, once released, is allotted a peculiar space, almost apart. Like a drop of serum injected in the veins of a solitude old by a hundred years, it stirs sentiments, sometimes it stings and sometimes it elates, in a worn-out body that has long grown habituated to living without its presence.

Back in the day when socialism still wielded magic and held the promise to bring bliss to nations and peoples, the Syrian regime purported to borrow the Soviet mode of organizing cultural production, in parts or in whole. To the contrary of their Soviet authenticators, however, the Syrian regime did not populate its cities and villages with movie theaters, playgrounds, parks, nor was the production output sustained. As early as its beginnings, the public sector drifted from these foundational premises, seceding to forge its own experience. Encumbered with the good intentions of their producer, our films come to life, step by step, drop by drop.

And yet, in spite of our poverty and of all the implications that a third world state- sponsored film production entail, the National Film Organization has produced thirty-six films in thirty-seven years, all of a distinguished artistic and intellectual standing, that have earned a total of seventy-two awards, internationally and in the Arab world. There is a real paradox between the historical conditions in which films are produced and the final out- come of the films themselves.

The paradox can be traced to the inner workings of film production, the kitchen of the institution so to speak, where films are made. There, a counter-intuitive redress of the injustice of the paucity of material resources takes place, and at times with rare generosity. As such, Syria might very well be the last place in this world where a filmmaker is given license to re-shoot a sequence until it is deemed right, where time and space for editing or sound mixing of an entire film can be redone, without a reconfiguration the film’s overall budget. Furthermore, Syria is perhaps the only place in this world where a young filmmaker without significant prior experience is provided the opportunity to make a feature-length film, regardless of the viability of the film once it is released. This generosity, which runs against the grain of the prevailing mores of our century, comes at a high cost. The tremendous burdens of producing a single film, or a film and a half every year is shouldered at the expense of an output that would sustain a dialogue with spectators, with our society. Syrian cinema is trapped in a conversation with itself, an eerie monologue that the National Film Organization (despite its hard labor) has failed at bridging into a dialogue with society at large, year after year.

And time knows no mercy. Generosity not withstanding, we all pay the wages of backwardness and poverty, and there are most likely, hundreds of talents craving for air to breathe, and for opportunities to find expression; they lie in waiting, time slowly extinguishing their flame. In this third world of ours, creative innovation and genial ideas dwell in gestation, in their largest share, hostage to poverty and backwardness. I have always lived with the belief that Fellini’s groundbreaking approach, for example, must have long been dreamed in the imagination of a captive soul in our part of the world.

Its generosity not withstanding, the National Film Organization has turned its back on venturing into creative solutions to alleviate the weight of its mission.

At a time when we are unanimously convinced that only works of art and the language of creativity are able to obliterate, through dialogue and communication, the sinister thick of backwardness, the tyranny of globalization and the insuperable polarization that pulls geographies apart, the National Film Organization has turned its back on every opportunity at co-production and cooperation that has frayed its passage to Syria. Under the guise of protecting the self-styled “purity” of its mission, it has cowered in its destitution, hostage to fear and suspicion. And so we too remain, suspended in that atrophied space; with our hopes and dreams we struggle for air.

The National Film Organization regards collaboration with European counterparts as the road map for colonization. The argument goes like this: How could countries that once colonized us, or coveted our riches with colonial designs be attributed good intentions. Europe does not really recognize Israel’s occupation of our territory as a crime, and they have absolved Zionism from the occupation of Palestine, the expulsion of its people from their homes. Europe does not see Zionism as an ideology of terrorism. How can we collaborate hand in hand with countries that defend all these crimes?

These facts are true, and I would go further and deepen the notion of terrorism, it should not be restricted to opening fire, setting up checkpoints or administering violence. Terrorism is also the violent death that comes packaged in a hamburger and vetoes the implementation of UN Security Council resolutions. The flaw in the argument is not in the veracity of the evidence it lists, but in the question it asks. Firstly, it presumes that European countries, their governments, their civil society, their intelligentsia and their cultural actors are all one and the same block. As such, it imputes the same agency and intentions to all these distinct and independent entities. Secondly, it presumes that the mandate of cinema and film production is to oversee (or lobby) fer the implementation of UN Security Council resolutions. It does not regard cinema as the sovereign site for existential interrogation by individuals and collectivities, for forging freedom and unveiling life’s small secrets, lived and imagined.

A conversation with the world is the only (and most effective) strategy afforded to the quixotic musketeers of the Third World. The absence or failure of that dialogue is a loss to the entire world, east and west, it compounds the toll of global poverty because the riches of culture cannot be plundered, usurped, or seized like oil or diamonds. Our countries may be stunted in abject poverty, but we claim novels, poems, music and films unsuspected by the western world, marvels that bring so much wonder they lengthen a human being’s short life by at least a few years.

Amongst their accomplishments, Americans and Europeans claim airplanes that break the sound barrier, state of the art technologies of extermination and stealth industries of well-being and leisure. This does not imply that their poetry is superior, their imaginary more sophisticated and their commitment to life, dignity and justice more legitimate than ours. I am aware of the hard reality and that with the resources at her or his disposal, the American and European artist is able to chase her or his flights of fancy, while our wings are clipped by the weight of historical contingency, and our dreams or flights of fancy remain folded in our shirts. However, at the risk of sounding like a missionary for culture and the arts — and I don’t consider myself an intellectual —, it is my unshakable belief that art and culture are the realms where humanity finds freedom, justice and equality.

Before you are allowed into the American Cultural Center in Damascus, before you can grab a seat to listen to Richard Peña, the director of the New York Film Festival who has traveled all the way to Damascus to deliver a lecture, you have to pass through the metal-detector at the gate of the building and endure a security search. In a single stroke, all the curses against imperialism dormant in the back of your head, awaken suddenly and growl. In one fell swoop, you find yourself emboldened anew in solidarity with Che Guevara, the massacred victims of Maï Laï (the Vietnamese village) and slain Iraqi singer Nazem al-Ghazali. Richard Peña, or Richard the First as we re-christened him that day, began with boasting his Spanish and Latin extraction, but he made an observation on Syrian cinema that struck us all. He postulated that the common denominator to all Syrian films, regardless of artistic accomplishment, was their independence and individualism, and the absence of opportunism. In the whole lot of Syrian films, he could not find a single propaganda film. This, he added, was a unique virtue. “Not a single film, Mr. Richard?” you find yourself asking. “No,” he replies to you in English. That Richardian assertion led me to reflect on the conversation that binds us all, we Syrian filmmakers, that lonely monologue I deplored earlier. How could we have missed seeing that common denominator? My perception of our collectivity until then was that we were generally divided in two camps. The camp that despises a colleague’s film because it does not fulfill the standard of what is considered to be art, and the camp that does not care and dispatches film and filmmaker to hell. In reality, and for the sake of precision, we are divided into at least seventy camps, the camp of those of who tell the truth fearlessly versus the camp of the hypocrites, the camp of the honest versus the camp of the dishonest, the camp of those adept at grabbing opportunities, the camp of those who know how to bluff… We are indeed the cultural vanguard of our society, and its backwardness finds expression in our collectivity in many ways. We manipulate, philosophize, theorize, each single-handedly scheming in the pursuit of self-interest. And thus we divide and multiply to form seventy camps, seventy voices each singing its own tune.

Standing on the field of the final battle that defeated Spartacus, the Roman general asked the captured black slaves: “Which one of you is Spartacus?” The noble freedom fighter rose and said: “I am Spartacus.” I remember weeping in the movie theater, compelled with his courage and nobility. But then, one after the other, the black slaves stood up and said: “I am Spartacus!” “I am Spartacus!” I wept more and more. They were all executed. Would you consider me a Spartacus, me the Syrian filmmaker (now also philosopher), if I were to make a confession? That everytime the National Film Organization prepares to consider a new (single) production, and each one of us knows it could be the one and only chance to make a film, I begin daydreaming the appropriate scenario for my colleague, whose name is on the same list and has been waiting for that one and only chance as eagerly as I, to perish in a noble yet untimely death. (The very same colleague I embraced just a moment ago, and who embraced me back.) Martyred after a savage air-raid shelling by the American-Israeli F-16 or F-17 planes (despite the fact that he had nothing to do with the Nazi crematorium or European anti-semitism)? Crushed under the brand new tires of a speeding luxury vehicle driven by the precious progeny of a nouveau riche patriarch (the very cast of nouveaux riches created by the veto on the UN Security Council resolution)? Of course I would be the first to deliver the compelling eulogy, a poem in classical sonnets. I would do more, I would dedicate that one and only film of my career to him. I am not the only protagonist in this real-life noir, and I am certainly not the most evil.

This is why Richard the First’s observation was striking. He did not see our opportunism. He saw us as honest filmmakers. Had we developed a singular strain of Machiavellianism, I wondered, were we sinister opportunists to whom the end justified all means, but the moment our hand grabs hold of the camera, we become honest and conscientious filmmakers? In truth, our circumstances are dire and the stakes are very high, because we don’t apprehend opportunities as merely the occasion to make another film, but to articulate our subjective vision of the world, to speak and innovate our individual cinematic language. This hunger for expression is the key to unlocking the paradox that mystifies all those who stumble on the productions of our National Film Organization. We are fierce about speaking our minds, it is our right, our raison d’étre.

Our right as filmmakers to innovate and explore, to craft our art according to our vision, to reconfigure our society and national aspirations according to our own pulse and sensibility, is what animates our cinema. We understand the very personal to be very humanist, and to be the other face that coins the very patriotic, and very universal. This is the confession in its totality, it is what has allowed Syrian cinema to cast the national anthem in the most forbidden, impenetrable and unsuspected places, to the surprise of all.

It is premature to distill attributes of an identity to Syrian cinema, in the way Italian, French or American cinema have carved identities for themselves. The identity of Syrian cinema is yet in its embryonic stages, growing slowly, alone, at the rate of one film per year. The common feature thus far palpable, is the motivation of its filmmakers for a tireless search, in the self, the social, the political, the aesthetic. That search has been its salvation from mediocrity, from aping other cinemas and pandering to a calling lesser than art. The National Film Organization is unfortunately the only haven for making films that meet the ambitions of cinema as art. It would be a mistake to regard it as the contingency itself, rather, it is the result of the overarching contingency that shapes the fate of our country. It is not right that it should hold monopoly over film production, but this is the reality today. And today too, it seems worn out from exhaustion, like a tire churning to come unstuck from mud, or a film reel beaming into emptiness: at once tangible and ephemeral, not unlike mercy.

The National Film Organization is the progeniture of our regime, its cadres are the sons of our state, and so are we, the filmmakers, sons of this nation. In the circus showcase of life we chose the tightrope, despite the dangers, because we wanted to make sure the rope would be stretched, that thin rope hinging between reality and imagination, freedom of expression and artistic creation.

Our cinema is free, but its freedom is like a whisper in a closed room. We too are free, but locked in an enclosure, the historic contingency that weighs over our sky. It is as if we sneaked into that closed room from the keyhole, and we grew inside it. In its turn, it sneaked inside us and grew. And we are stuck in this locked embrace.

On the outside of that enclosed room, the invitation to jump ship and join television production lurks with insistence. It is like the call to surrender and negotiate a truce: “Come to television, your voice will be heard, instead of your metaphors and alle- gories and that art, you will be seen, you will have a presence, you will make a difference.”

The city of Homs, which grew irritated with its football team’s lot of continuous defeats against its arch-rival team from the city of Hama, tells a popular Syrian joke. The residents of the city raised millions of pounds to sign the star player, Maradona. The Homs team was defeated once again, this time, by the humiliating score of 10 to 0. “What about Maradona?” someone asked. “The coach kept him on the sidelines” came the answer. And one morning, Pushkin, the Russian poet, went to meet his fate at a duel. Revolver to revolver, not poetry against Tomahawk. But poetry was still in the man’s heart. And coffee is coffee, not tea.

Epilogue

I will conclude with an anecdote, also popular in Syria. In a world competition amongst cats in the world, the expert-trained American cat was defeating every cat he fought with. The last confrontation had him duel the Somali cat. To everyone’s surprise, the Somali defeated the American. There was much alarm in America. The White House issued orders to increase training of their contender and a second match was called. The American cat was defeated a second time. After much consternation, president Clinton invited the Somali cat for a closed-door meeting. “How were you able to defeat the cleverest, smartest and best-trained cat in the world?” he asked. “Look at me, Mr. President” said the Somali cat, “look deep into my eyes. I am not a cat, I have never been one. I am a tiger, but hunger and poverty made me look like this.”

The text was presented by Ossama Mohammed at a conference organized by Georgetown University in 1999.