ArteEast is pleased to present an interview with artist Yasmine Nasser Diaz as part of our Artist Spotlight.

Yasmine Nasser Diaz is a multidisciplinary artist whose practice weaves between culture, class, gender, religion, and family. She uses mixed media collage, immersive installation, fiber etching, and video to juxtapose discordant cultural references and to explore the connections between personal experience and larger social and political structures. Born and raised in Chicago to parents who immigrated from the rural highlands of southern Yemen, Diaz is interested in complicated narratives of third-culture identity and their precarious invisibility/hyper-visibility.

Diaz is a recipient of the Harpo Visual Artists Grant and the California Community Foundation Visual Artist Fellowship and has works included in the collections of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, The University of California Los Angeles, and the Arab American National Museum. Her work has been featured in HyperAllergic, Artillery Magazine, and Kolaj Magazine. She lives and works in Los Angeles. Yasmine is represented by Ochi Projects, Los Angeles, CA

ArteEast: Can you discuss some of the main themes in your practice?

Yasmine Nasser Diaz: Much of my practice draws fairly directly from my personal experiences and delves into themes around third-culture identity, feminism, gender, religion, and collectivist/individualist tensions. The lens of my more narrative work is often that of a US-born Yemeni girl– that may sound very specific, but what I’ve continuously learned in sharing the work is how universal these experiences are at their core. The details and methods of delivery may be more familiar to some, but the root sentiments are understood by many.

AE: You’ve worked in a variety of mediums such as collage, neon, and installation. Do you use different mediums to convey messages or emotions? If yes, how so?

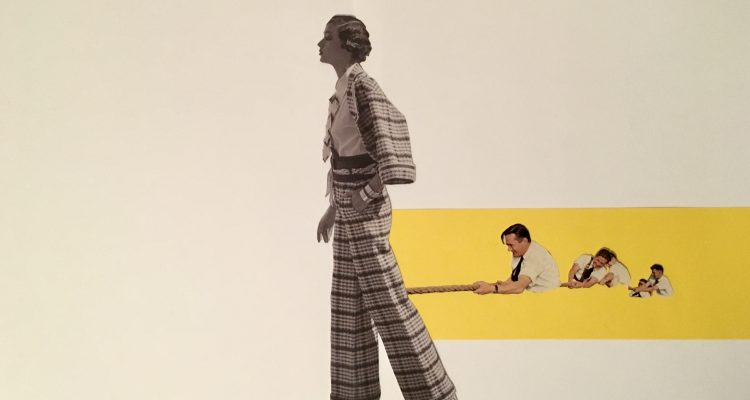

YND: The transitions from one medium to the next have happened organically while thinking about how to effectively deliver different ideas. About five years ago, I was preparing for a significant shift in my practice and I was struggling with how to talk about some very personal and vulnerable issues for the first time. I decided to use collage after I began experimenting with it and was reminded of how playful and liberating a medium it can be. I especially loved the parallels between what collage inherently is and what it means to hold third-culture identity, essentially mash-ups of sorts. Installation has allowed me to construct intimate and familiar spaces while simultaneously holding details of the unique individuals who fictionally inhabit them. Neon is bright and loud, and for those reasons, I knew immediately that I wanted to use it to inspire dialogues that we have been discouraged from having.

AE: You’ve recently developed a new body of work consisting of fiber etchings. How did you develop this series and how does it fit within your overall body of work?

YND: My main bodies of work incorporate the use of personal photography and collage, and the fiber etchings are essentially translations of the same type of snapshot photography. I was increasingly incorporating imagery of textiles as well as scraps of actual fabric into my collages when I came across some old photos of family members wearing a Yemeni dress made with burnout fabric. The more I looked into it, the more the material and the reductive process by which it is made resonated. Burnout, also known as devoré, was popular in the 90s when I was a teenager, and it’s also the time period that much of my work focuses on. The dress I mentioned, a dir’, is understood to be worn by married or engaged women. My work in soft powers centers adolescence and more specifically, Yemeni-American girlhood. So, it hit a lot of marks for me. I ruined many pieces of fabric while learning the process last winter, but it was worth it. I love the play between opacity and transparency. This is something that I, and I think many marginalized people, consider often. What information should be included? How much should be explained, and who are we considering?

AE: You’ve begun collaborating on several projects with other women artists from the Middle Eastern (SWANA) diaspora. What do these communities of artists represent to you and how has this affected your practice as a whole?

YND: This new community has become a kind of growing chosen family, and it’s incredibly meaningful to me. Growing up, I felt extremely isolated in our Chicago-Yemeni neighborhood. The values I was developing were at extreme odds with those of my family, leading to an eventual long-term separation. I didn’t see my family for many years, and I encountered few people of SWANA background as I bounced around the country for a while. It took a long time for the weight of ‘3eib’ or ‘what will people think’ to start shedding before I was ready to speak about my identity and background through my work. Thanks to social media, as I shared this work and my own story, we—my fellow SWANA misfits and I—began to find each other. What slowly began as mutual admirers and followers on Instagram has grown into meaningful networks of support and, in some cases, creative collaborators. Most importantly, I think there is a growing realization that we are not so much the fringe but the norm.

AE: You’ve approached sensitive topics within your work such as 3eib and haram* culture within both a larger Arab context and within a more specific Yemeni framework. Could you elaborate on the difference between the two, and why these themes have been important for you to address?

YND: In the past couple of years, I’ve spent time in the Detroit-Dearborn area, home to the largest populations of Arabs in the U.S. There are large communities of Lebanese, Iraqis, Syrians, Palestinians, Yemenis–you name it. What I found really interesting was that, even though the Yemeni migrant community there had existed much longer and was significantly larger than the one in Chicago, compared to the other Arab groups, it remained more insular. This resonated with my experiences growing up in Chicago. While we certainly share cultures heavily influenced by the social conditioning of 3eib and haram, the close-knit nature of the Yemeni community perhaps magnifies some aspects of collectivist culture. I think that both individualist and collectivist cultures have their double-edged sword qualities. In my opinion, the value of 3eib and haram is one of the more harmful aspects that can be exacerbated, perhaps even more so in diasporic communities.

Addressing the harmful effects of 3eib culture and the disproportionate ways it impacts women and girls is central to much of my work. Unless we unpack it honestly, there’s only so much progress we can make towards achieving gender equality and ending patriarchal violence.

*The notion of shame in Arab culture (3eib) and what is forbidden, often with regards to a sexualized context for practicing Muslims (haram)

YASMINE NASSER DIAZ ONLINE:

Website: yasminediaz.com

Instagram: @yasmine.diaz