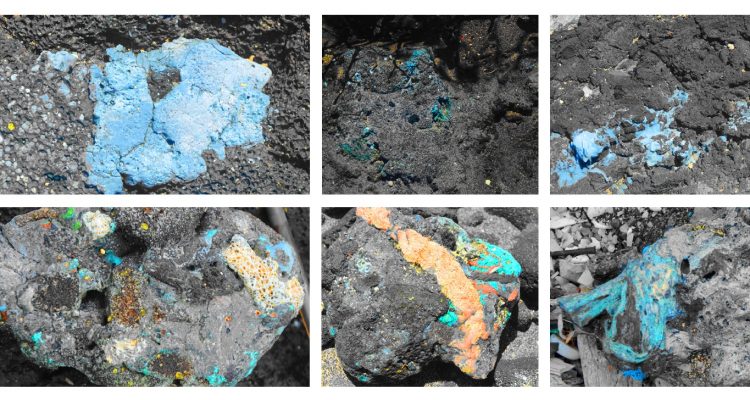

Manipulated images from collected samples of plastiglomerate rock material found on the polluted Kamilo beach in Hawaii.

Manipulated images from collected samples of plastiglomerate rock material found on the polluted Kamilo beach in Hawaii.

More than twenty years ago at a United Nations conference on climate change, governments met to agree on a defining strategy in the fight against the weather. As previous attempts at reducing our carbon footprint had been deemed unsuccessful, the new position was a defensive strategy of the utmost rigor. This strategy was “defensive” in that it was dependent on technological innovation to halt, reverse, and counteract the wrongdoings of rising temperatures. It was regarded as the most practical approach, and one that would not compromise economic growth. Following this treaty, more than ever before in the history of humankind, technological prowess was considered to be the only hope for humanity to survive on the planet.

This development paved the way for radical solutions, such as releasing synthetic organisms into the atmosphere to deliberately alter our environment. Through absorbing carbon dioxide or reflecting sunlight, such terraforming processes were seen as a way to cool the planet. Consequently, our planet became encapsulated by an artificial layer of invisible, self-regenerative, synthetic organisms. They came to be known as our most sophisticated army of terra-drones, only perceptible from the ground on bright days as black dots, and maintaining and regulating climate control from the sky.

The techno-utopia that emerged benefited from an upsurge of economic prosperity; production and consumption were on the rise, and the consequential increase of waste was dealt with through the most advanced recycling techniques.

These days, Beirut has overcome its unfortunate history of recurrent waste management crises, dating back to the first quarter of the 20th century. At the time, inhabitants of the city, in order to clear their neighborhoods of piles of trash, had developed the bad habit of burning it, disregarding its toxic effects on the environment. As a consequence of this intensified period of burning waste on roadsides, along the empty riverbed, on beach shores, and under highway bridges, the whole territory of Beirut and its environs is now well-known to be a rich depository of a specific type of rock formation colloquially referred to as “plastic stones.” This rather new type of rock, a blend of plastic and organic matter, was first discovered in 2006 along the shores of Kamilo beach in Hawaii, a result of beach bonfires. The substance, termed plastiglomerate by scientists, is more resistant to decomposition, reminding us that when we burn our trash―full of plastic―we only make synthetic matter more durable and resistant to aging. It is predicted that once buried within the strata, these future fossils will endure for millions of years, becoming a trace of humanity’s time on earth.

Based on pure speculative imagination, the projected vision of the region in a million years is that of a rich archeological site, full of this specific type of fossil. A landscape formed of bleak cliffs revealing the stratification of peculiar bright colors; rocks lying on the beach with veins of synthetic yellows and blues, perhaps as gay and colorful as our supermarket merchandise.

Today’s ultra-modern recycling techniques for dealing with plastic waste are heavily inspired by the phenomenon of the plastiglomerate. Technology has been developed to find ways of blending plastic waste with other recycled materials in order to generate new composite materials. These are mainly used to substitute natural stone, which has become rare and expensive. Those new composite materials clad the surfaces of our buildings, sidewalks, and walls. As a result, the exoskeleton of our cities are covered and ornamented with colorful patches of synthetic materials.

More than ever, man-made materials are undergoing a process of symbiosis with the natural environment, and the distinction between organic and synthetic matter is growing hazy. It has become common practice to introduce artificial enhancement within our bodies, our minds, and our everyday objects. Man and the built environment are both evolving in a similar way towards a synthetic and digital hybrid, an inevitable fusion of flesh and technics.

Miniature artificial intelligence systems enhance brain activity by allowing it to absorb knowledge and information rapidly. Similar operating systems are integrated into static objects, such as furniture and walls, to enable constant connectivity and data exchange. Books still exist as nostalgic memorabilia, but their physical use is long obsolete. Reading is an old habit very few have interest in. Information infiltrates our brains in less than a minute and is stored into our satellite memory hard drive. This is extremely beneficial to our evolution as a species, since concentration is no longer a human virtue; it is rather a technical supplement.

The processes through which plastic stones are manufactured provide an excellent design solution for embedding digital chips into static matter in a discreet, non-intrusive manner. Plastic stones are molded into a specific shape that allocates space for these chips. Objects, walls, and furniture listen and record our conversations. They also speak to us. We all are aware that everything one says is recorded, even though surveillance cameras are no longer visible. The surfaces of our cities are covered and ornamented with colorful patches of synthetic matter of an intelligence far beyond that of most humans.

…

She waves her hand at the monitor to shut it down. It’s not the first time she watches this episode. She’s always been fascinated by history, and so she revisits this program to be reminded of the long way we’ve come since her parents’ days. Her favorite part of the documentary remains the part filled with futuristic images of colorful cliffs by the beach. This vision of a deserted, sandy beach triggers feelings of unease she is unable to explain. Perhaps it’s because she could never afford access to one of those beaches, even though she lives close to the sea. She puts on her jacket, slips on her comfortable shoes, hurriedly glances at the mirror to fix her hair and heads out. As she walks down a busy shopping street of interactive vitrines, she suddenly stops and leans against a wall. She feels dizzy from the intense smell of jasmine flowers. She has developed a sentimental addiction to the smell of wild jasmine after listening, numerous times, to the story of a woman who used to pick them and place them in her bra throughout the day. Every night, as this woman took off her bra and got ready for bed, they would slowly fall to the ground, while the smell would remain on her breast all night. Inspired by this story, she has a vision of small jasmine flowers magically dripping in between her breast. She has never felt the texture of a jasmine flower. Nonetheless, she can see it and smell it. Thanks to her integrated nostril filters protecting her from occasional bad scents, she can regulate the surrounding odor through a mere cerebral command. She would always pick the scent of jasmine while listening, over and over again, to this particular chapter of the story on slow dictation mode. One day, she decides to realize her dream of sitting in a garden full of jasmine, and recreates a vision of this magical garden through software that allows her to project the view inside her bedroom. She slips on her virtual contact lenses to experience the 3D view on her walls, full of greenery and small white flowers. This makes her happy, until she gets closer to stroke the plant. Nothing. Her fingers hit a smooth slippery resin blotch on the wall.