Ali Cherri, Still Life, 2017, Lightbox, Duratrans Photographic print, 150x90cm. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Imane Farès

Ali Cherri, Still Life, 2017, Lightbox, Duratrans Photographic print, 150x90cm. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Imane Farès

Decades ago—in the absence of art fairs, commercial galleries, independent arts organizations, private collections, and government initiatives—artists in the Arabic-speaking countries of West Asia planned exhibitions, symposiums, workshops, and biennials. In addition to contributing artworks, they formed curatorial committees, acted as jurors for art prizes; worked as fundraisers; and often covered or reviewed these events for local newspapers and publications. Artists not only forged this history, but also recorded and preserved it. Unlike their counterparts in Europe and North America, whose roles as cultural workers diminished after World War II, artists in the Levant and the Arabian Peninsula continued to be active in shaping the foundation of local art scenes well into the second half of the twentieth century. This began to change in the early 1990s with the growing influence of curators and art administrators, in addition to the introduction of several nonprofit art spaces and government-led initiatives.

Between 1993 and 1999, contemporary art organizations like Ashkal Alwan (the Lebanese Association for Plastic Arts), Darat al Funun in Jordan, and the Al-Ma’mal Foundation in Palestine restructured the regional art scene by developing extensive programs that freed artists from the burden of producing exhibitions and perennial events while offering much needed support. As creative circles began to form around (or gravitate to) these platforms, nonprofits served as springboards for expanding the reach of local experiments and narratives, connecting artists in the region to international developments.

In the Arabian Peninsula, few government-funded projects have been as successful as the Sharjah Biennial. Although Kuwait was the first Arab Gulf state to offer art scholarships and studio spaces in the late 1950s, the United Arab Emirates has surpassed the modest efforts of its neighbors by building an elaborate art infrastructure that has been significantly expanded in the last ten years. While Dubai has transformed the regional art market with official patronage that caters to collectors, and Abu Dhabi aims to be the museum hub of the Arab world, Sharjah has focused on facilitating and encouraging artistic practices.

The first edition of the Sharjah Biennial was launched by the Sharjah Department of Culture and Information in 1993. Twenty years later, Hoor Al Qasimi—a trained artist and curator who is the daughter of the ruler of Sharjah—revamped the biennial by widening its scope. What was once largely devoted to regional painting and sculpture became a multifaceted program that brings together artists, curators, writers, and scholars from around the world. The biennial’s corresponding events grew in number and size in 2009 when the Sharjah Art Foundation was created and a more comprehensive program was developed as part of a broader government effort to make contemporary art more accessible. So far, the foundation has been able to meet the demands of hosting a popular international event while keeping its stated goal of prioritizing local aud

iences. This includes a strong emphasis on arts education that is open to the public, particularly school children that are invited to attend workshops, performances, and exhibition tours. Although recent editions of the biennial have reflected the strengths and weaknesses of their respective curators, the foundation has maintained an active role in setting the tone of its overall program.

Hiwa K, Pre-Image (Blind as the Mother Tongue), 2017, HD video, color, sound, 17_40 minutes. Courtesy of the artist and KOW, Berlin.

Enlisting Beirut-based curator Christine Tohmé to organize Sharjah Biennial 13 is intended to further its reach across West Asia with an emphasis on some of the urgent issues that are currently affecting the regional art scene, from the building of art infrastructures to the fluctuation of political climates. Tohmé, the founding director of Ashkal Alwan, has a long history of working with other arts organizations and cultural practitioners in North Africa and West Asia (including Hoor Al Qasimi, who serves on Ashkal Alwan’s Board of Trustees). Founded in 1993, Ashkal Alwan formed at a time when Lebanon had not yet recovered from twenty-five years of a brutal civil war, and young artists working in conceptual art, photography, video, and installation were in dire need of backing. Since its inception, Ashkal Alwan has regularly produced events that consider the difficulties of sustaining art scenes in turbulent political contexts, for example, working with artists under siege in Palestine, or more recently with those directly affected by the Syrian war.

Tohmé’s edition of the biennial is titled Tamawuj, an Arabic word that describes “a rising and falling in waves,” offering a metaphor for the region’s current period of uncertainty while also invoking the independent organizations, perennial events, and artistic circles that have shaped local art scenes. The biennial’s theme is deliberately open-ended, allowing for a range of topics to be addressed across different sites in the United Arab Emirates, and outside the country in Dakar, Istanbul, Beirut, and Ramallah, where lead curators and scholars were asked to respond to key words—water, crops, culinary, and earth—in the form of smaller events. With these offsite programs, the global ecological crisis is explored through the lens of a specific setting whereas reviews of the main exhibition in Sharjah (referred to as Act I) have noted its emphasis on informal networks, artistic interventions, and other types of exchange that offer means of survival in a world that feels like its crumbling. Unfortunately, a common complaint among critics is that the Sharjah presentation was slim on the work of Emirati artists, and therefore missed an important opportunity to comment on local conditions.

Upon a Shifting Plate, which is the Beirut leg of the Sharjah Biennial, is produced by Ashkal Alwan and will take place on 14th and 15th of October with events that explore how culinary practices are indicative of psychic spaces and cultural norms. Although available descriptions of the weekend’s schedule are vague, the biennial’s online publication, tamawuj.org, has released a number of related essays and texts ahead of the opening date that hint at possible topics, including how Lebanon’s ongoing political instability affects food consumption among different populations.

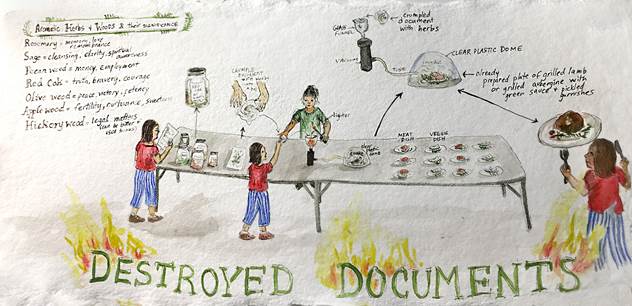

Candice Lin, sketch for Destroyed Documents, 2017. Watercolour and ink on paper. Courtesy of the artist.

For Act II, the second and final iteration of the Sharjah Biennial 13, Tohmé has commissioned curators Reem Fadda and Hicham Khalidi to create special exhibitions at the Sursock Museum and Beirut Art Center, both of which open on October 14. Responding to the biennial’s broader themes, the exhibitions are billed as its closing presentations. Of the two projects, Khalidi’s An unpredictable expression of human potential (on view through January 19th, 2018) appears most promising with a roster of artists who rarely show in the region, if at all. Working with associate curator Natasha Hoare, Khalidi offers a glimpse into the experiences of disenfranchised youth in North Africa, West Asia, and Europe, where institutionalized racism and overt class divisions are galvanizing a new generation of political activists, resulting in effectual forms of protest culture. The included artists all demonstrate a need to document and participate in this historic groundswell. An unpredictable expression of human potential departs from other projects in the biennial that seem to suggest artists and viewers step back in order to recharge. However, whether swimming against or with this wave of history, the concept of Tamawuj could be extended into other fields as a necessary approach to these difficult times.