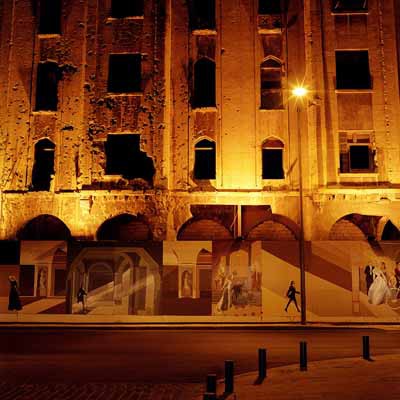

Greta Torossian, Boxes in ”Beirut 99: Real Visions”, 1999. c-print, 39 x 39 in

Greta Torossian, Boxes in ”Beirut 99: Real Visions”, 1999. c-print, 39 x 39 in

A white square ceramic tiled wall behind a big heavy machine juicing carrots and my impatient need to have that juice: this is the only vivid memory I have from Beirut’s city center before the civil war erupted in 1975. At that time, I was 6 years old.

During the last summer before the war, one night at our mountain house, I remember my excitement and joy for finally having a real camera in my hands (but with no film inside!) and carelessly/casually “shooting” the dinner guests while they were chatting on this big balcony that I love. The backdrop of this scene was the familiar velvety night view of some illuminated heights in Mount Lebanon.

My excitement was not only about using a real camera for the first time. I remember my almost euphoric feeling for having what I thought was an incredible power: to capture moments of real life and in that way being able to keep pieces of reality forever frozen in time. I felt like grabbing a moment of life much like picking a fruit from a tree. Pictures were more real than any drawing.

Greta Torossian, About-turn in “Beirut 99: Real Visions”, 1999. c-print, 39 x 39 in

Many years later, showing reality with photography took a whole new meaning for me. After being concerned with technique and aesthetics during a very classical academic program (while majoring in photography at USEK) I finally felt free enough to use photography as a means to express what I saw about life and the human being the way I really saw it. The truth in my mind was not in the details of the moment and I stopped being concerned with capturing the instant.

Du Corporel, my project on the human body marked the start of my conceptual approach. In it I chose to show the human body as the supreme architecture, where form acquires the symbol of the function (J. Starobinsky about L’Architecture Parlante). I wanted to show the concept of the body (without dismissing its carnal dimension) instead of being interested in showing the particularities of the bodies photographed.

Greta Torossian, Permit For the Future in “Beirut 99: Real Visions”, 1999. c-print, 39 x 39 in

The civil war has of course been nothing but a pain in all the meanings of the word, although I was fortunate enough to not lose a parent or relative in the war and being lucky enough to spend time in Cyprus for a few months during the worst episodes of the war. But I have also seen days where bombs fell on our one way street, or on my mom’s car. We have circulated in the car while bombs were falling not far from us or snipers firing. We have spent time in underground shelters. The one in our building was improvised in the small room of the heating oil tank.

The last time we fled to Cyprus in 1989 we were on nighttime fishing boats in the sea, with bombs falling around us. I was 19 years old then, I prayed on the second small boat to die rather than become handicapped. My grandparents were with us on the boat and my grandfather’s sick body was rigid due to his Parkinsons. Around a month before that day, six phosphorescent bombs had fallen on my father’s furniture factory and the whole place burned in one night. My dad’s lifetime work and everything he possessed was turned to ashes.

I see that after all, despite living through the whole civil war with all its consequences in the details of our lives, I didn’t see things differently than in their essence, whenever I thought about the war or wanted to express what I saw. Focusing on the victim or the pain is not what I think of when I want to denounce injustice or war with photography. I feel that transcending the victimhood and sentimentality allows for a more mature or more efficient message.

It seems to me that as a reaction to all the problems induced by the war in our lives, I had no interest in politics, or in supporting this or that party’s views or ideology. Honestly, it was easy for me to see all the politicians and parties as immature people playing immature games. Taking part in that game in any way was the stupidest thing for me, since I had experienced the bitter consequences of that game for so long.

Have I seen the war in general and in my photographic work differently than I would have if I was not Armenian by blood? Or, would I have seen things differently if during the civil war I was attacked by other Lebanese just because I am Armenian by blood? No, I don’t think that I would have seen this civil war differently.

Greta Torossian, Paradise in “Beirut 99: Real Visions”, 1999. c-print, 39 x 39 in

Architecture was the first thing I thought of in college. After my first year in architecture, we fled to Cyprus on a crazy boat adventure. Then, after a year of studying economics in Toronto, I suddenly thought of photography. I wanted a freedom of expression, and an artistic orientation.

Soon after graduating I was given a “carte blanche” by the French Cultural Center in Beirut for a solo exhibit with a catalogue. The director had loved my nudes project (Du Corporel), which was shown in 1998 during the “Month of Photography in Lebanon”. I had just started photographing the center city, and that became part of Beirut 99: Real Visions.

In fact in 1999, the contrast created in Beirut’s city center by the simultaneous presence of war/destruction remains and bold reconstruction/life signs held an absurd character that captivated me.

I told the director of the French Cultural Center that I had just started this project because I couldn’t leave these surreal views of brand new buildings juxtaposed to war torn ones, without recording them. And I was going to do it even if the photos were going to stay in my drawers. I think that this project was also a way for me to express the absurdity and immaturity I saw in the politicians and warlords all throughout my childhood. Exposing these absurd and hardly believable views with no human face in them frankly felt like I was exposing to them their own stupidity. But that was far from being my goal with the project, because I didn’t believe that my project would have any impact on any politician. And I must say that if these views were anywhere else in the world and I saw them, I would have thought of making the same pictures.

Greta Torossian, Way Towards the Past in “Beirut 99: Real Visions”, 1999. c-print, 39 x 39 in

As I earlier mentioned, I had not sympathized with any side during the war. Needless to say, in this project I was on nobody’s side. The damage done and the pain endured in our lives was too high, I felt, to justify any party’s views, even if there was a genuine approach to Lebanon’s integrity and sovereignty.

Today, I see corruption in politics everywhere, so politics and politicians are not of any interest for me. Politics are necessary for the world we live in, not anything I see of moral value.

It happens that the views containing both destruction and reconstruction in the Beirut of 1999 were also a good reflection of the specific character of the Lebanese capital, as Beirut is famous for being the city of contrasts in many ways. Throughout my childhood I had over and over witnessed the thrust for life and resiliency of the Lebanese people: they didn’t stop partying and living as fully as they could during the war. My reaction to this was to notice the absurdity that the human being can create in life.

Greta Torossian, Permit For the Future in “Beirut 99: Real Visions”, 1999. c-print, 39 x 39 in

My project Creating Land is about a Beirut suburb’s artificially created landscape. I think that urban landscapes are a great reflection of the human state of mind.

I did An Absence in the Presence because the empty streets and spaces of Beirut’s Martyr’s Square after the 2005 demonstrations only showed the strong presence of late prime minister Hariri’s spirit in the hearts and minds of the people.

I think that the act of putting your view/sensitivity in a photograph is an exercise you do by yourself and first of all for yourself. Can there be total honesty in a photograph if the photograph is made with others in mind, instead of a total surrender in the act of the creation?

Maybe this is why I don’t believe that art can radically change other people’s minds/views.

Like many unknown artists (before or even after their death), Van Gogh painted mainly for himself.