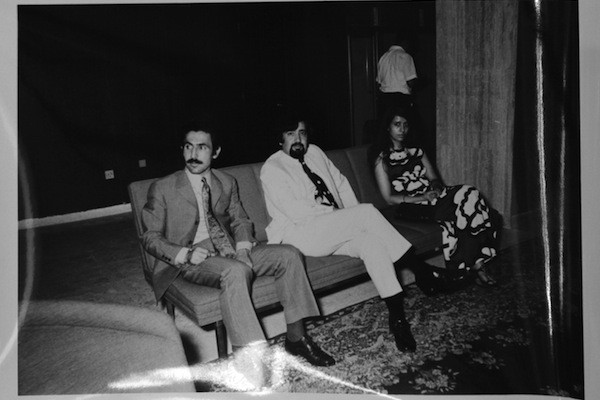

Iraqi artist, Dia al Azzawi with Ghazi and Najat Sultan, 1969.

Iraqi artist, Dia al Azzawi with Ghazi and Najat Sultan, 1969.

The Sultan Gallery is an art gallery initiated by brother and sister duo, Ghazi and Najat Sultan, who opened the gallery in 1969 in Kuwait City, and which closed with the Iraqi invasion in 1990. With a mission to promote and exhibit “modern young Arab artists,” the gallery was the first of it’s kind in the Gulf, and took its inspiration from galleries in the Arab world, a network of which it was a central part in the 1970s.

The Sultan Gallery was reopened in 2006 by Farida Sultan, Ghazi and Najat’s younger sister who was involved in the latter part of the gallery’s life. Though in a different location today, the gallery supports both local artists, and exhibits both Arab and international artists, and holds the archive of the gallery’s previous iteration. This rich archive, rare in it’s kind and condition, served as a starting point and main source for the development of research around the history of the gallery and its work, part of an ongoing research project about the development and display of Arab art in the 1970s. In mapping institutions and events of that period, I hope to tell a different story, through infrastructure, of the development and expansion of a regional art scene in the 1970s.

My methodology is grounded in both archival research and interviews with individuals who were a part of the gallery in its early years. In 2012, during a month long research residency with ArteEast at the Sultan Gallery, I had the privilege to spend time in the archives unearthing documents which uncovered stories about the gallery: its role and links in Kuwait, connections beyond the city, and unrealized projects, among countless of other types of documents, photographs, correspondences, and material. The archive allows the beginning of the writing of an institutional history, but what it contains in its meticulous records also help us draw the lines of a regional and international art scene of which the gallery was a part.

In addition to archival research in Kuwait, I performed interviews with individuals who had a stake in the gallery, which included different members of the Sultan family, and others who have been residing in Kuwait since the 1960s or 1970s and were perhaps a visitor, buyer, friend, or artist of the gallery or the founders. In addition, over the last couple of years interviews with other interlocutors outside Kuwait, mostly artists who had shown exhibited at the gallery, or gallerists or other actors from the scene at the time, who had been living or live in cities including London, Amman and Beirut have helped tell the story, through individuals, of the impact and significance of the gallery in their own work.

The research residency concluded with an exhibition organized by myself and Farida Sultan, entitled The Founding Years (1969-1973): A Selection of Works from the Sultan Gallery Archives, exhibiting artwork and documents from the first 5 years of the gallery’s exhibitions, to be a starting point to look at the period of Arab Art through the lens of the gallery’s role in its development, a story which had not been previously told or presented to the public in a long format.

In this essay, I do not to try tell all the stories that arise from the gallery and its work, or the work of its founders, but rather intend to give an introduction to the origin of the gallery’s establishment, and map the gallery into an Arab-regional network, inscribing it into a map of other Arab art galleries, and artists in the region; This map is an often overlooked and under researched network which exposes a newly regionalized art scene, with galleries and artists, artists unions and ministries of culture ranging from Baghdad to Beirut, Kuwait to Casablanca. The people behind initiatives, like the Sultan Gallery, played a key role in expanding and developing a regional scene, while in the case of Kuwait, it placed Kuwait alongside other cities exhibiting Arab art, allowing the work of artists to travel, and spurring the development of collections.

Though I don’t present the research in this essay, the Sultan Gallery’s story must also be integrated into a local/Kuwaiti context of artistic development—as a catalyst for not only collection building but also cultural education and part of a larger scene with other actors. The gallery’s international links, to that of India and beyond deserve reflection, as well as a proper history of the work of the founders, Ghazi and Najat, as well as Farida Sultan. This is in addition to the actual work and practices of the artists who exhibited at the gallery. I hope that in time, I am able with others, to convey these other stories about the gallery’s work and its founders. This essay though, is a starting point, maybe that of an oblique one, to enter into the history of Arab Art of the period of the 1970s through the doors of a small gallery with a long-lasting impact.

The Founders

Leila al Kazi, a friend of Najat Sultan, recalls that Najat was the go-to woman for advice and mentorship for young educated females and those interested in politics or feminism, especially for those who were returning to Kuwait. She went to Najat after her own return from college and was introduced to the gallery which opened up a new world and discovery of a community which has been quite transformative for her. This is just one of the stories about Najat’s impact in the local community. In fact, Najat was one of the founding members of Kuwait’s National Council for Arts and Letters, modeled on the UK Art’s Council, and she was a founding member of its arts directorate and served as the head of the directorate. Among that, she founded the Sadu house, a site where traditional Bedouin weaving was taught and preserved, an art form that was being lost at the time. As a Pan Arab nationalist, she grew to know and support culture of the region she hailed from but didn’t grow up in—she and her siblings were raised in India, as many merchant families from the Gulf were living in India at the time.

Ghazi, Najat’s older brother, had studied architecture at Carnegie Mellon and Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, and returned in the summer of 1968 to work in architecture. He worked at an architecture firm and built both private residences and public projects around the city, and over the years came to be known as one of the notable architects of his time. He was known as the main figurehead of the gallery, while Najat worked more quietly behind the scenes.

“Modern young Arab artists”

The gallery’s stated mission was to exhibition the work of “modern young Arab artists” and after Ghazi and Najat’s travels and interactions with artists, they felt that they could contribute to supporting artists, not to mention in a place where these artists were completely unknown, in a city that was newly developing in the decade of the 1960s. The context of Kuwait is important, as it was a newly modernizing city, growing and changing rapidly, and Ghazi and Najat found the opportunity to contribute to its building.

In a document penned by Ghazi, he mentions that those [Arab] artists were “generally overlooked by their societies” while there also, inherently lacked in the Arab world, the proper encouragement for the arts. They had a frustration with over-bureaucratic Arab governments that did a poor job in exchanging and sharing “contemporary art and craft from one Arab country to another.” This meant a weak network of artists, and artistic exchange, which they wanted to change.

The Sultan gallery was not a full time venture for either Najat or Ghazi, they both were occupied with their other professional work as a teacher and architect, and they called the gallery a “professional hobby” and a family-run project. This was in contrast to other galleries, namely in Beirut which couldn’t guarantee the continuation of the gallery due to the lack of support. They would be able to sustain it through a family support, but this wasn’t a vanity project, and was and is still cited as the most professional galleries that artists remember to this day, with contracts signed between the artist and gallery. So it’s title as the “first professional Arab art gallery in the Gulf” is deserved. In fact, one story told was that some members of the family had a gentleman’s agreement that they would purchase a work from every exhibition, so sustainability was guaranteed on one level.

A loft and the Inaugural Exhibition

Among the new buildings, in the city center was the Thunayn al Ghanim building on the Sheraton roundabout, named for the new hotel built the same decade. The Sultan Gallery’s neighbors included a barbershop. Two brothers, whose parents were friends of and buyers from the gallery, shared two memories of the gallery: getting their hair cut as children next door, while their parents hung out at the gallery, and a photo of them both distributing chocolates at an opening.

Another space in the ground floor of the building was occupied by the Kuwait bookshop, a center for intellectual life, and one of the few places to purchase books in languages other than Arabic.

The Sultan Gallery occupied a tiny storefront, and the space had a sort of loft/office space upstairs, which Ghazi designed himself.

The gallery’s walls were a thick weave of a raffia/jute , making it feel a bit ethnic, and with a lot of character.

In the lead up to the first exhibition, Ghazi and Najat had done their research, through their networks of friends, artists, and architects ranging from India, Beirut, Baghdad to London but chose to inaugurate the space with a two-man show (the rest of them were one-man shows).

So, on March 21st, 1969 under the patronage of the head of the state, the emir, of HE Sheikh Abdullah Al-Jaber Al-Sabah, the gallery was inaugurated with artwork by Kuwaiti Munira Al Kazi, and Iraqi, Essam El Said, both of whom lived in London and were friends of Najat’s (and well respected artists).

El Said was born in Baghdad and grew up there, though completed a degree in architecture at the University of Cambridge in 1961 and resided in London. Al Kazi was born in Pune, India, as her family was also a large merchant family of Saudi/Kuwaiti origin, and she had studied at London’s Central School of Art and Design graduating in 1961.

Neither artists were present for the exhibition but by a huge crowd of not only Kuwaitis but foreigners alike and marked the beginning of an era of Arab art for Kuwait. Ghazi notes in a letter to Essam that the exhibition was a huge success, though it was clear that the “maximum premium” people were willing to pay at that point was approximately 50 pounds for an artwork, explaining why paintings did not sell as well as the etchings and prints.

City to City to City

The gallery’s focus, as was stated, was to support modern young Arab artists, and the gallery, over its lifetime, showed artists from Iraq ,Kuwait, Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Morocco, Algeria, Palestine, and Saudi Arabia. Ghazi and Najat both traveled, but the archives only map out Ghazi’s travels, as he was in charge of communications at the gallery. They responded to a weak regional network by building their own.

The arts infrastructure of the region was also dotted in the 1960s and 1970s by art galleries showing local artists in Baghdad, Beirut, Damascus, Casablanca, Rabat, Cairo, with some cities like Beirut and Baghdad boasting more. Pan-Arab galleries and spaces showing artists from beyond the country’s borders proliferated in the 1960s and 1970s, with Gallery One in Beirut (1960), Dar al Fan (Beirut) to Gallery Nadar in Casablanca (1967) and L’Atelier (Rabat, 1973), along with Contact Gallery in Beirut (1972), and then of course, the Sultan Gallery in Kuwait (1969).

The Sultan Gallery was in direct contact with a number of these spaces, while the archives also point to other events and initiatives, like the First Arab Biennial in Baghdad, 1974, to conferences in Damascus and Baghdad from the early 1970s, contact and mailing lists map out artists, intellectuals and architects in the region who served as contacts.

In 1969 Ghazi traveled to Baghdad, where he met with Said Mathloum, one of the founders of Al Wasiti gallery and an architect, a renowned gallery showing Iraqi art, and who was his entry to meeting the majority of young artists working in the city at the time, many of whom are now considered canonical artists from Iraq, and the region. The country with the most representation of artists showing at the gallery during its 20 years is Iraq. Artists exhibited often multiple times, and the second show hosted was that of Dia Al Azzawi,among others. Including Rafa Nasiri, Hashim Samarchi, Shaker Hassan Al Said, and Nuha al Radi.

Just a couple of months later, the Sultan Gallery opened, and after that, in the summer of ‘69, Ghazi embarked on a “discovery tour” as he called it, to the major Arab capitals, traveling to Amman, Beirut, Cairo and Damascus where he met with, artists architects, and gallery owners.

Egyptian artists who exhibited include Salah Taher, Mohammed Mousa, Gazbia Sirri, Abdulwahab al Morsi and Yehyeh Sweilem.

He met with Fateh Moudarres in Damascus who showed later in 1969, and Ghayas al Akhras showed several times in the early years.

While in Beirut met with Youssef al Khal from Gallery. The archives contain some material from Gallery One, including this poster of Saleh Jumaie, who exhibited later at the gallery.

Gallery One was one of the major art galleries of Beirut in the 1960s, whose artists most overlapped with the gallery, taking contacts and inspiration of how the operated and displayed work. As it was, the artists would often show in their home cities, as well as in Kuwait and Beirut during the same year. Lebanese artists who exhibited include Farid Haddad and Amine el Bacha, among others.

Continued travels over the years point to how the a few other artists came to exhibit: correspondences indicate that a visit to Morocco in 1981, in particular to two galleries, L’Atelier and Nadar in Rabat and Casablanca respectively led to the exhibitions of Egyptian Adam Henein and Lebanese artist Etel Adnan.

A trip to Rome in 1970 led to the meeting of Mohammed Melehi, who later showed at the gallery. Laila Shawa, Palestinian artist exhibited in the early years, while other local artists who exhibited include Bassil al Kazi, Souad al Essa. During the gallery’s 20 year run, they had nearly 100 exhibitions.

Through the archives of the Sultan Gallery, one can map important nodes of the Arab Arts infrastructure, from galleries to artists, unions, and events, where exchange between countries, and across borders developed more rapidly in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Arab Art as a category developed at this time, coming from and being defined from within the Arab world, by artists, cultural managers, and intellectuals, as a break from national identification. The Sultan Gallery played a major role in the Arab art scene at that time, and the reverberations of its work in the local and regional context can be told through the collections built in Kuwait, coming out of a commitment by two individuals in supporting a growing artistic scene, which spanned across several countries.

A quick note of thanks to ArteEast, Barrak Al Zaid, Farida Sultan and the Sultan family in their help and commitment to this ongoing research project.