Bilingual English/ Arabic art publications, Cover photos pasted on wood, various format collected by Fehras Publishing Practices, 2015-16

A few months ago, we at Fehras Publishing Practices began looking at a phenomenon of the past decade we refer to as “the transformation of modern Arabic in the context of the rise of Arab cultural institutions”. Our focus and interest in the transformation of Arabic is part of a larger research titled Institutional Terms, a project that concerns itself with the emergence of a language specific to bilingual art publications issued in the last decade in the EMNA (East Mediterranean and North Africa) region. Our research is structured around four topics: bilingualism, institution, translation, and the production of cultural dictionaries.

We began by collecting art publications issued between 2003 and 2016 by cultural institutions in the region. While reading and analyzing their material, our attention was drawn to new and singular ways of using Arabic on the level of form, terminology, and syntax. Drawing on personal impressions, we concluded that the first step towards understanding this unfamiliar use of Arabic was to look at the way our own collective used language.

From the outset, language and writing—both fundamental parts of publishing and artistic work— have played an essential role in our practice. While outlining the premises of our publishing house and embodying them in text, we were faced with the following questions: In which language should we write and publish? Who are the readers and viewers of our work?

After careful consideration, we decided to publish in both Arabic and English, writing all original texts in Arabic and translating them to English. Meanwhile, problems began to surface. We were quickly confronted with the difficulty of transferring and translating art and publishing terminology from English into Arabic. We doubted Arabic’s ability to express our ideas, not to mention the frustration with the limits of our own vocabulary in our own language, Arabic. We found ourselves entangled between the two languages. Another concern of ours was form and design: what kind of aesthetics did bilingualism produce?

The cultural institutions established in the 1990s across the EMNA region, specifically in cities such as Cairo, Beirut, Marrakesh, as well as several cities in the Gulf peninsula, have undergone tremendous changes in the past decade. Since their establishment, artistic practices that have emerged within the region have contributed new discourses.

While browsing publications and catalogues, we came across numerous scholarly articles and conferences that dealt with art from the “Middle East”. Many critics agreed that the growing interest of the West in Arabic and Islamic culture was connected to September 11 and to the general expansion of a globalized art market; the discovery of “Arabic modern art” as a promising investment sector for private capital in some countries (or for both private and public in others) contributed to an increase of cultural institutions in the region. Through invitations, residencies, and funded projects, artists and cultural producers were given the chance to travel globally and therefore play a greater role abroad.

Bilingual English/ Arabic art publications collected by Fehras Publishing Practices, 2015-16

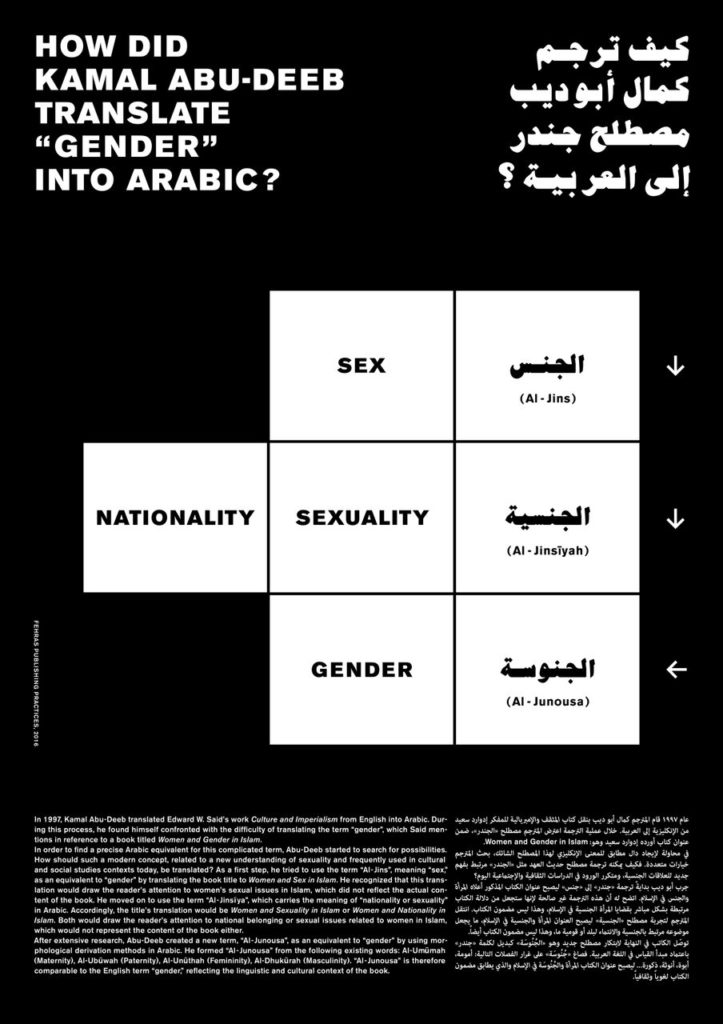

Though most of the printed matter accompanying this expansion used English as a global art language, many institutions insisted on keeping their material bilingual. While reading bilingual publication, titles in unfamiliar and awkward Arabic phrasings, terminology, and syntax caught our attention. Was it only a matter of a poor translation?

In most publications, Arabic and English mirror each other; they begin at opposite ends of the book and meet in the middle. Attempting to create a balance between both languages, the layout follows a symmetrical principle, printing texts in similar sizes and across matching page numbers. The thematic focuses include exhibitions, projects, and symposia. Prefaces, interviews, biographies and researches generally offer poorly translated contemporary art writing attempting to transfer content into an Arabic cultural context.

In their Arabic translations, these texts often exhibit language experiments in fusha, playing with Arabic’s classical structure and inventing new terminology modeled on western discourses. We underlined and excerpted terms that sounded unfamiliar in Arabic and tracked their equivalent in the English essays. We later classified and arranged them under various discourse categories such as the body, globalization, public space, gender, etc.

Discourse Flash Cards (“Body”), collected and indexed from the following publications: Globalisation and the Manufacture of Transient Events, 2003. Photocario 4. The Long Shortcut, 2009. Indicated by Signs, 2010. Towards a New Cultural Cartography, 2014. Final Vocabulary, 2015

The transformation of the Arabic language mentioned above can’t be divorced from the role cultural institutions played in shaping its production and use. Art publications always accompany curated exhibitions, meetings, and symposia. They become crucial to institutional strategies of artists promotion and project documentation. Looking back at 1960s and 1970s, art publications were often used as a means of institutional critique whereas today, they have become institutional tools. Their role is to document projects and exhibitions, feeding and fueling the machinery of institutional production.

To better understand the production process involved in art publications, we compiled detailed lists gathering imprint information such as names of authors, artists and curators, editors and translators, funding sources, occasion for publishing, year of publishing, languages, designers, publishers, and ISBNs. Drawing up lists revealed a complex global co-production system comprising various players, institutions, local spaces, cities, languages and western founders. For example, the book Susan Hefuna Pars Pro Toto released in conjunction with exhibitions in Cairo, Alexandria, and Dubai in 2008 and funded by Deutsche Bank and Goethe Institute in Gulf Region. Another example is the publication of the visual art project Indicated by Signs which was presented in Cairo, Bonn, Beirut, and Raba in 2010 and funded by Goethe Institute. Or the publication Unmade Film which was released in Jerusalem, Paris, Zürich and Southampton and funded by Al-Maamal Foundation for Contemporary Art in Jerusalem, Centre culturel suisse in Paris, Les Complices in Zürich, and Jon Hansard Gallery in Southampton.

Bilingualism and translation play critical roles in understanding the web of transaction governing contemporary art production, and bilingual publications raise urgent questions concerning translation, its methods, and purposes. Since the rise of postcolonial studies, translation is no longer merely a linguistic tool but can be considered as a political and cultural instrument of representation. Bilingualism in art publications isn’t restricted to linguistic matters and terminology. It reflects structural power relations; how can a discourse that emerged in a specific cultural context be transferred and represented in another? Could translation be where the power of one culture over another demonstrates itself in language?

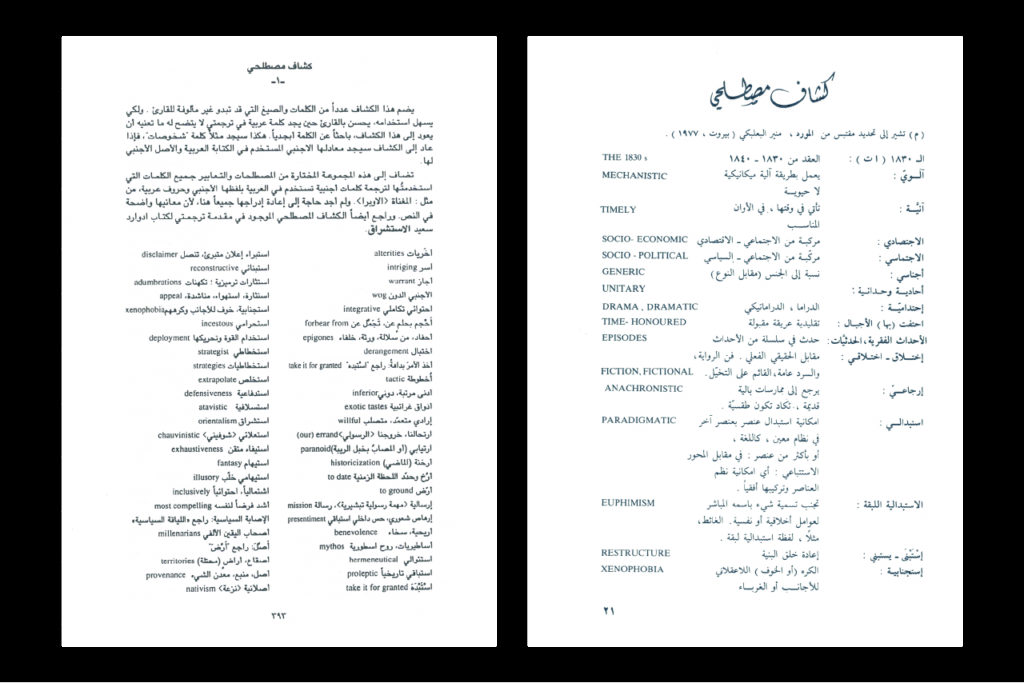

When conceiving the series Institutional Terms, we came across two historic documents, namely “Index of Terms” (“Kashaf Mustalahi”) created by the Syrian author, translator and poet Kamal Abu-Deeb indexing the Arabic translation of Orientalism (1981) by Edward W. Said, and Abu-Deeb’s translation of Said’s work Culture and Imperialism (1997).

Pages from Kamal Abu-Deeb’s “Index of Terms” in Orientalism, 1981 and Culture and Imperialism, 1997 by Edward W. Said

Pages from Kamal Abu-Deep’s “Index of Terms” in Orientalism, 1981 by Edward W. Said

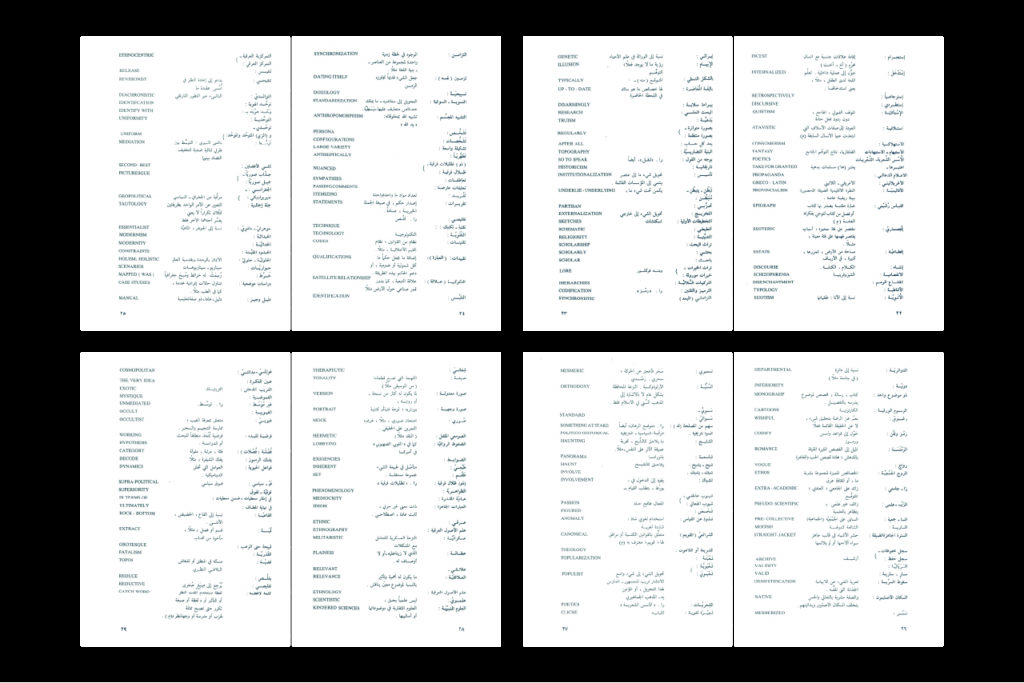

The first “Index of Terms” is placed at the beginning of Orientalism and the second, at the end of Culture and Imperialism. Functioning as an introduction and conclusion to both books, each index contains a list of English terminology and its Arabic equivalent partly taken from the Al Mawrid dictionary and partly created by Abu-Deeb himself by following specific rules. The translator considers his two indexes an adventure and experiment within the structures of Arabic. His kashafs (indexes) not only aim at representing Said’s discourse by simplifying and fitting it into an existing Arabic structure and terminology, it also offers a chance of extending, enriching and developing Arabic’s indigenous structure. The new terminology and vocabulary Abu-Deeb introduced were confusing to Arabic readers and translators at first. Nevertheless, these terms have now spread and are widely used across different disciplines and discourses. The translation method Abu-Deeb developed enriched Arabic from within, but to what extent does an Orientalist critique — namely, the production of a language emerging from western discourses— apply to Abu-Deeb’s translation itself.

HOW DID KAMAL ABU-DEEP TRANSLATE “GENDER” INTO ARABIC? A poster describing the linguistic methodology used by Kamal Abu-Deeb while translating “gender” from English to Arabic, DIN A1, Fehras Publishing Practices, 2016

Abu-Deeb used dictionaries and publishing as a venue to disseminate new Arabic words. What impact did Arabic cultural dictionaries have on writing the history of art of the EMNA region? What connections exist between art production and art historiography? How does linguistic production shape cultural knowledge and practices?

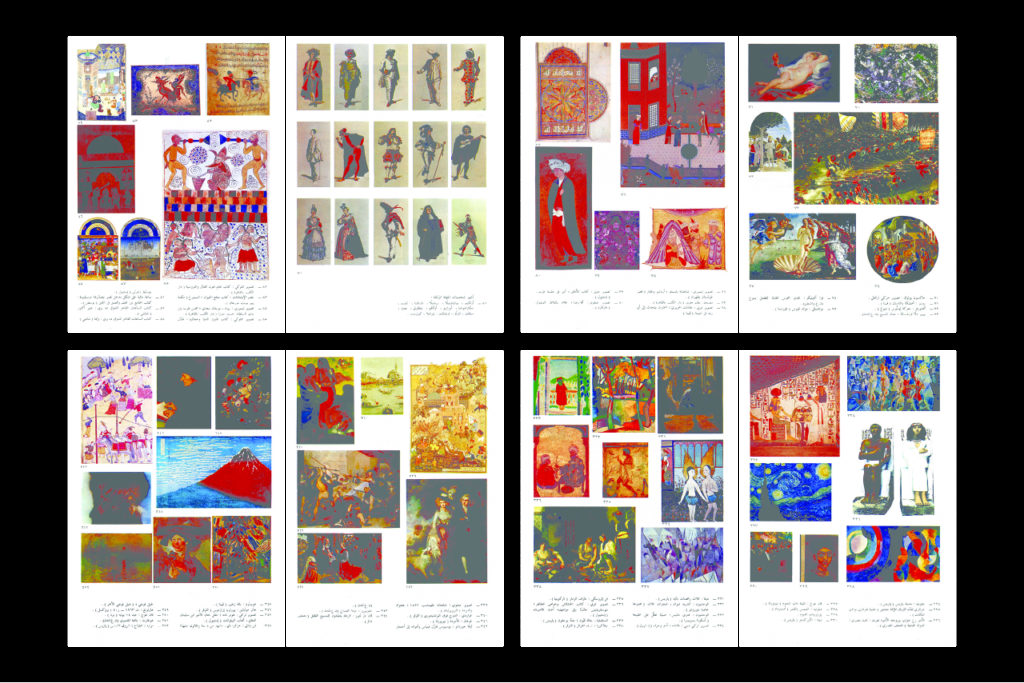

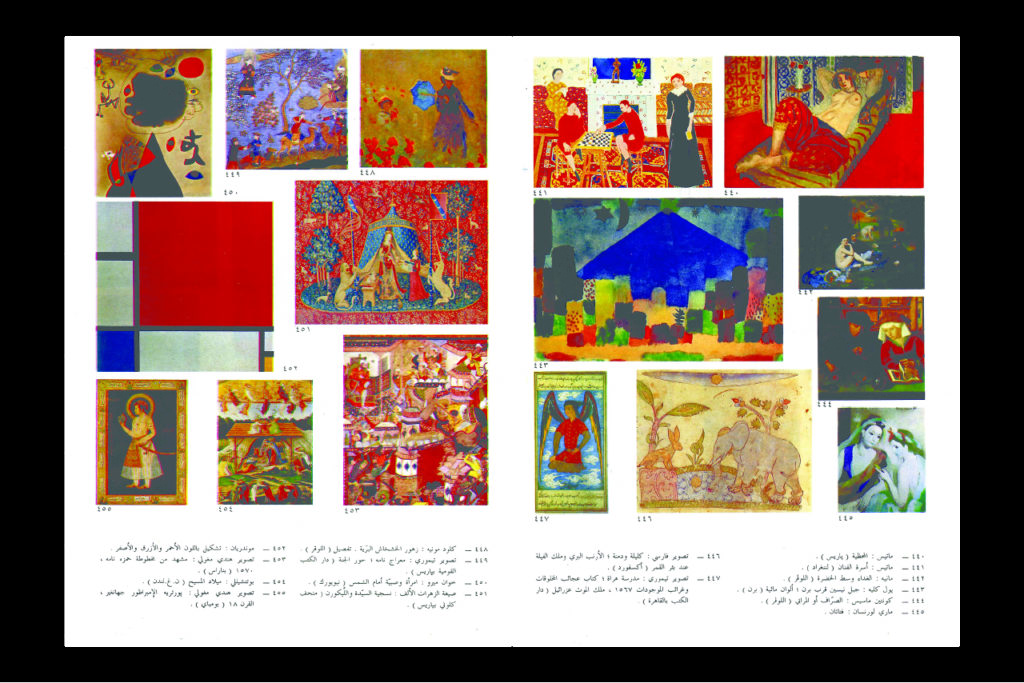

While observing the past of cultural dictionary-making in the region, we came across the Encyclopedic Dictionary of Cultural Terms, a dictionary created by the Egyptian art historian, writer, and translator Sarwat Okasha in 1990. This dictionary has an appendix that contains an 80-page “Index of Illustrations” prepared by Okasha. Most of the illustrated pages cover European art history up to the second half of the twentieth century. However, this same repertoire only covers ancient art history in Middle Eastern and Asian cultures!

Pages from Sarwat Okasha’s “Index of Illustrations” in Encyclopeadic Dictionary of Cultural Terms, The Egyptian International Publishing Co. Longmon/ Librairie du Liban 1990

Pages from Sarwat Okasha’s “Index of illustrations” in Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Cultural Terms, The Egyptian International Publishing Co. Longmon/Librairie du Liban, 1990

Bilingual art publications, the experience of translation, the formation of new terms as well as the production of cultural dictionaries and its relation to artistic work and art historiography all intersect in a web of complex relations involving knowledge transfer and power structures between cultures.

This space is where language is produced, published, and disseminated. In spite of these intersections, each publication carries its own specificities.

Abu-Deeb’s translation of Orientalism and Culture and Imperialism, for example, has the difficult mission in transferring sensitive discourses questioning the relation between east and west into Arabic. More than a simple task, translation becomes the very field in which orientalism is played out. It challenges Abu-Deeb to delve and research the internal structures of Arabic. He was thus driven to the creation of new rules, searching dictionaries and creating new ones in order to disseminate his terminology.

Bilingual art publications generate new terminology in Arabic and its usage in a cultural context. However, most of the translated essays give the Arabic reader the impression that the translation process is merely technical; it lacks will and invention. It tends to be subordinated to the dominating discourse. This turns an essay or a publication into a self-contained unit divorced from a larger linguistic field as well as similar examples of art and cultural writing.

Our research doesn’t aim at defending classical Arabic rules, but rather at questioning the nature of the produced language in art publications as well as the circumstances surrounding it. Art publications possess the power of mobility inside the global art context. Their production involves different players, cities, and institutions. Moreover they embody the space where discourses and language are being published and disseminated. They play, therefore, a crucial role in writing Arabic modern art history today.

Institutional Terms is concerned with the creation of an institutional Arabic language uncritically used, globally shared, and mostly determined by cultural funding policies.

What are the possibilities, however, of experiencing a linguistic alternative outside of cultural institutions today? There is an urgency and need for the creation of a language representing an Arabic cultural discourse that is not only the product of a global art language but that also accounts for and is in dialogue with different fields such as literature and science. This change comes with the responsibility of researching language, developing terminology, and understanding the act of translation in its political and social dimensions. In publishing terms: to what extent can art publications —the child of institutional language — be a means of critique and generator of language and art?

Installation view from the exhibition Mirroring Language, Extending Dictionaries, from the group exhibition Something to Generate From, Fehras Publishing Practices, Kunsthal, Aarhus, Denmark 2016