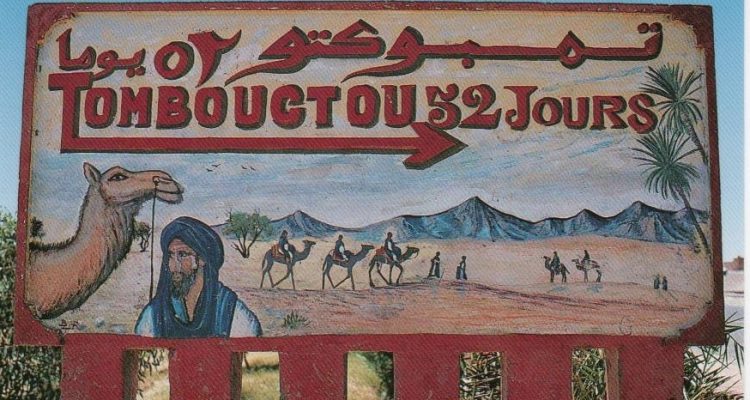

"Timbuktu, 52 days", a painted sign in Zagora, Morocco.

"Timbuktu, 52 days", a painted sign in Zagora, Morocco.

Deserts fascinate me—they have for the longest while, particularly the Sahara. Perhaps, it’s the idea of the existence of life amidst so much aridity and desiccation, or the co-existence of desert and oasis, two states held in tension by an inherent opposition, which mutually heightens their individual essences: the desert becoming more desert because of the idea of the oasis and vice versa. Perhaps, it’s the idea of the Sahara being a ruin of what was once a verdant, green land, which continues to harbour some form of life and to expand. Whatever the reason, for the last several years a constant companion on my bedside table has been the book Deserts[1] whose title is self-explanatory and which attempts to explain the ecosystems of the major deserts of the world. Every so often before falling asleep I’ll open it, thumb through the various sections, and invariably I would find myself turning to the section on the Sahara. It is, therefore, with some trepidation and repressed excitement that I’m following the driver of the mini-van who had arrived in the early hours of the morning at the riad in the Medina in Marrakech—I’m headed for an overnight visit to the Sahara—for two days and one night, most of which—some fourteen hours there and back—will be spent on the road. The kindly hotel manager who had organized the trip for me had cautioned that if I really wanted to see those sculpted red or yellow pillows of sand, which I do, and whose images I have feasted on over the last few years before going to bed, I would be better off making a four day three night trip. I can’t—I leave Morocco in three days. Where I’m going, he says, Zagora—otherwise known as the Gate to the Sahara—will not satisfy those longings, but it is still the Sahara.

I trail the driver down the narrow street only wide enough for carts and the cats, arrogant and elegant, who stalk past me, tails erect in the brisk morning air. I’m carrying my two bags—the driver’s apparent lack of willingness to help me with them doesn’t bode well and my anxiety increases when I notice his somewhat dishevelled appearance—I can see the top of his underpants where his shirt has become caught in the elastic. Why does that bother me?

Ten minutes later we pull up at what is clearly the central meeting point for the many buses making trips to the Sahara, and primarily through gestures I’m directed to another bus—it’s larger, more spacious, and fully air-conditioned with windows in the ceiling—which will be the one to take us to Zagora. At 7.30 I’m the third person on the bus—the other two are a couple; I say hello to them, they say nothing in response. I sit behind them in the window seat in the last but one row and over the next half an hour the bus slowly fills with passengers.

It’s the tone of voice that first grabs my attention—a mixture of superiority, condescension and officiousness that exists in all the languages of empire, its owner a mature-looking white man with lightly greying hair. He stands outside the bus and addresses the driver: “Are you sure this is the right bus? I’m doing a three-night-four-day trip.” The bus driver assures him that he is. He lets us all know that he’ll be joining another trip the following day and takes his seat behind the driver. I dub him Rational White Man and make a mental note to avoid him.

It is during this time also that a young couple gets on—one sits next to me in the row of double seats, the other right across the aisle from her companion in the row of single seats. We smile at each other and say hello—they’re from Latin America, they tell me, he from Argentina, she from Peru. They speak English fluently, she with a posh English accent that must have cost a lot of money. I decide that once we’re all settled I’ll suggest that we switch seats so that they can sit together—that way I can still have a window seat and stretch my legs out.

I observed him coming down the aisle not knowing that I was his target, the man who now stands before me and speaks to me as if I am an animal: You, he says, move! He glares at me as if I’ve done something wrong. The brute force of his command is as severe as if he had punched or slapped me. Why? I ask, even as his crude, assaultive command stuns and shocks me. In response he points and gestures for me to go up front and sit next to Rational White Man in the last remaining empty seat—it’s clear that he wants the young couple next to me to sit together. I hadn’t known that there was a rule that couples must sit together. They say nothing. I suggest to them that we switch seats, which I had already intended to do. I resent the way the man has spoken to me and am deeply disturbed by what has just happened, but I take a deep breath and settle myself in my new seat.

The engine of the bus turns over; we, some fifteen passengers, all strangers to each other, are about to set off on the seven-hour journey that will take us to Zagora, when suddenly, as if summoned by the sound of the engine, two youngish white women suddenly appear outside the door of the bus. Consternation grips the group of men gathered outside the bus who all appear to be somehow involved in the trip and ripples out—there is one empty seat on the bus and two passengers have shown up. Some of the men talk on cell phones, others appear to argue with each other; one of them has a clipboard and seems to have some supervisory function.

I sense rather than observe anything directly, as if what I’m apprehending is happening below the radar: is it the glance thrown my way that I notice through the corner of my eye by one of the men? Was it from the man who had come on to the bus and spoken to me as if I were an animal? I don’t know, but all at once I know what is going to happen; in every fibre of my body I know it and knowing it I wait, all my senses poised—on alert, like a snake coiled in anticipation of attack? The two women who were the last to show up stand outside the bus chatting and laughing; I am struck by their utter confidence and relaxed air. They seem not at all concerned that there was a problem—they are happy: I call them Happy White Girls—Happy, Happy White Girls.

Suddenly he, whoever he is, is standing before me—is it the same man who had spoken to me earlier—as if I were an animal? I don’t know, but he’s demanding I get off the bus and go to another bus. I know that once I get off of that bus they, these men gathered outside the bus, have no interest in what happens to me. I know that because I am the only Black person on that bus. I know that because Rational White Man, like me, is travelling alone but they have chosen not to approach him. Instead, they have chosen to approach me and demand that I leave the bus. I know that because, unlike everyone else on the bus who is going to the desert for one night, Rational White Man is going for three nights and, as he announced on his arrival, is picking up another trip the following day. Logically, he should be the one to be reseated on another bus. I know that because these men believe that the two white women who have showed up late are more entitled to be on the bus than I am. Finally, I know that because of the way the man first spoke to me—as if I were an animal.

I refuse. I tell him I’m not leaving the bus. He glares at me clearly taken aback—what he had expected is not happening. He turns and leaves. My refusal creates more consternation. Passersby gather on the edges of the crowd as the arguments and phone calls continue. Rational White Man and Happy, Happy White Girls are chatting among themselves. I don’t recall exactly when it happened but at some point the man with the clipboard addresses Rational White Man: What about you? querying whether he would leave and go onto another bus. Rational White Man is sitting behind the driver so he has a clear view of the bus the man with the clipboard is pointing to. He asks where the bus is going and points out that there is no one on board—he is reluctant to leave until he knows more, which I agree with. The man with the clipboard turns and leaves in exasperation. Rational White Man calls after him: If you leave like that we can’t settle the matter. He’s in full, rational mode now, reasoning with the emotional native.

They’re trying to work out whether they have to reimburse one or two tickets, he says in his continuing conversation with Happy, Happy White Girls who are still laughing and talking outside the bus, confident that they will be seated: herein lies the power and privilege of whiteness—its ability to insulate and cushion itself against the fluctuations and mutability of life, even when, as in the present situation, it was they who had showed up late.

Out the window the bickering and heated talking continues and before I know it another man has come down the aisle to me. I sense a growing frenzy in them as if my refusal makes them more determined to impose their will on me: You speak English? he demands. As if my refusal to comply with them is somehow linked to my linguistic ability to comprehend. As if racism needs a language to exist; as if racism were not a language on to itself. I do, I reply. Come, he says, you must come with me. And my body wants to comply with his order—I want to get to my feet, tell them all to kiss my black arse and leave that bus. My default response is to walk away from situations that cause me pain, and this situation is desperately causing me pain, humiliation and anger. But I know that this is what they want—these men, these brown men whose ancestors and forebears had themselves been colonized by France, by white men, but who are themselves as racist, crudely racist, as their erstwhile white oppressors. I had no doubt that the only reason they targeted me was because I was black and female and nothing they had done so far had given me any reason to believe other than that.

I knew, however, that I was not getting off that bus; I knew that they, the men outside the bus, the police, whoever they were, would have to drag me off that bus. They would have to lay their hands on this black, female body, so demeaned and derided by a history that knew no mercy, and physically remove me—it was the only way they were going to get me off the bus. But they didn’t know that—not yet.

I put my hands up chest high, palms facing outwards: I was the second person on this bus, I say, and I’m telling you, I’m not getting off this bus. He retreats. Everything is a whirl in my mind but there is a stark clarity about what I’m prepared for. Rational White Man and Happy, Happy White Girls are still talking; the men outside the bus are still outside the bus, talking and arguing heatedly. Passersby linger, some stay.

It could not have been very long but suddenly there is yet another man standing before me—the third. Was it my imagination but they seemed to be getting bigger. This one had jowls with an afternoon shadow that shook as he spoke—how many more would come?

You, as belligerently as the others, you have to come with me. Orders, commands—these would have been the linguistic staple of the plantation—language stripped to its bare necessity. At least I understood what they were saying. Was this a victory of sorts, or merely the workings of a well-oiled, exploitative tourist industry? Whatever the reason my resistance was forcing them to use a foreign tongue, also my foreign tongue, albeit my mother tongue. I raise my voice, loudly telling him exactly what I’ve told the other two, that I’m not getting off the bus and I resolve that when the next one comes, I will raise the issue of race. I will tell them what I’ve known since that first man spoke to me as if I were an animal—that they were targeting me because I was black. Why hadn’t I raised that issue before? Was I afraid of being accused of playing the race card? But the race card had been played a long, long time ago by the European in the wake of his encounter with the Other—after he had disrupted and unsettled the entire world. It continues to be played.

Through the window on the left I observe a bus pull past ours; someone from the group of men says to Rational White Man that that was his bus and he appears more satisfied than he was earlier. He stands, takes his knapsack and prepares to leave but not before looking directly at me and shaking his head—As for you, he says, and for a moment so brief I might have missed it I believe he supports me: What can I say?

What could he say, indeed? That he regretted what had transpired in that bus? That he supported my standing up to the men who tried to throw me off? That it was fine with him to switch buses and that he wished me a good trip. But that would have meant his breaking with his historically prescribed role of Rational White Man and joining with me—a potentially revolutionary moment; he simply could, or would, not do it. As he passes by my window he continues to shake his head: he’s clearly pissed with me and understandably so. After all, he, Rational White Man, had to leave the bus and I, the Black woman, had refused my historically assigned role of being the one to be thrown off the bus. No thanks to him, the Moroccan men, or my fellow passengers, all of whom had remained chillingly silent.

Happy, Happy White Girls, still laughing and talking, are now ensconced in the two seats behind the driver. One of them has her bare foot perched on the bar right behind the driver’s seat twiddling her toes. Is it o.k. to have my foot here? she asks disingenuously. He says it is. It always is, isn’t it—whiteness always has a space made for it in the world: I had just spent the past twenty minutes strenuously resisting being thrown off the bus, because they had shown up late, and here she was with her bare foot casually advertising and exercising the overwhelming privilege her skin grants her in this world.

We are finally on our way, but I have no idea how I will spend the next two days with people who have witnessed my humiliation and shaming and have said nothing and done nothing. My mind turns to 1781 and the massacre by drowning of enslaved Africans on board the Zong so that the ship’s owners could collect insurance monies. This tragedy would become the subject of my 2008 book-length poem, Zong!, performances of which over the last few years have led me to explore examples of African healing practices developed in the face of trauma: Gnawa music, originating in Morocco, is one such example and is the reason I am in Morocco. The ironies do not escape me—234 years after the Zong tragedy whose rationale was the profit motive, attempts had been made to throw me off a bus to ensure that the bus didn’t travel with an empty seat. Race and the profit motive, the fulcrum of so much of history’s trauma, leads me to think about the costs of racism: I had paid the same fee as all the other passengers on that bus for an overnight trip to the desert, yet the non-monetary costs to me, emotional, social, psychological and otherwise, had been inordinately steep.

Once we are on our way, I take out my journal and begin writing about what has just happened. No more than half an hour into the trip Bob Marley’s War comes over the sound system, which has been playing music ever since we left and I am outraged. In 1963 the Emperor Haile Selassie addressed the General Assembly of the United Nations about the scourge of racism, particularly in Africa; Marley set his speech to music: until the philosophy/which holds one race superior and another/inferior/is finally/and permanently/discredited/and abandoned/everywhere/ is war/me say war…. War became a Rasta anthem that spread around the world becoming a song of liberation in post-colonial, Afrosporic communities, and here I am listening to it on a bus in Morocco after one of the most egregiously offensive displays of racism I have had the misfortune to be subjected to. I want to destroy the equipment playing the song and lament the digital age because my violent imagery of destruction entails pulling out wires and breaking CDs. War, indeed!

My thoughts are dark, ugly and not worthy of being documented here, but Rosa Parks surfaces and without making any equivalency between the enormity of the struggle she came to represent and the more individual nature of the “event” or “situation”—I don’t have the right word for what had just happened—I had been involved in. Where did she go, within herself, that is, when she decided not to give up her seat for the white man who demanded she move? Was it similar to the space I went to—a space of deep black mystery (not in the racial or political sense) which offered a deep sense of certainty?

Later, when we make our first stop, I and the young Peruvian woman who sits across from me are the last two on the bus: she needs to put on a blouse before going into the café we stop at. Of her own accord she expresses concern for how I was spoken to—I come from a developing country, she says, and that is the way they talk to people. I am overwhelmed because someone has witnessed what has happened and has acknowledged her witness, although she had been silent all along. I, too, come from a developing country, I fire back, and we don’t speak to people like this. This was nothing but racism—I say, plain and simple. She’s taken aback—Oh do you think so? I suck my teeth and turn my face to the window and weep.

The trip would have an unfortunate end for a couple of the other travellers— an older, Dutch man, travelling with his daughter, fell off his camel and broke his hip, giving rise to the possibility that he could lose his leg. It was sobering. Perched on my camel, waiting for over an hour for an ambulance to arrive, I could only feel compassion for him—it could have been me.

It was me.

[1] Marco Stoppato & Alfredo Bini: Deserts (Firefly Books, 2003)